In a world of increasingly mass-distributed advertising, you would have to be living under a rock to not be bombarded by more than a few ads for personality quizzes online, in the newspapers and otherwise.

You might have even jumped on the bandwagon and taken one or two and if not, at least been remotely interested in the idea. But where did the seeming necessity to define ourselves in this way come from? Why can’t we seem to resist taking personality tests?

The roots of personality testing can be dated back to the 18th and 19th centuries during which one’s disposition was measured by studying skull size and other physical aspects of the face. But I think it’s fairly obvious these early tests lack both reliability and validity.

“Humans are 99.9 percent identical in their DNA; we differ only in .1 percent, which not only attributes to our physical differences but also our personality differences,” said Rima Najm-Briscoe, professor of psychology at Sonoma State. “In my opinion, physical differences [appearances] do not tell us much about who we are.” With a Ph.D. in psychology, Briscoe’s words certainly hold more than a little weight.

Luckily, those earlier aesthetically-based formulas were amended with preferably pragmatic modern methods by the start of World War I when the U.S. Army created a self-report inventory called the Woodworth Personal Data Sheet to determine whether or not draftees would be predisposed to shell shock. Not long after the introduction of self-report inventory personality tests, the invention of projective tests, which measure a person’s presumed hidden emotions and conflicts through his or her response to ambiguous stimuli, added another level of accomplishment to the field of personality testing.

There are several notable, psychologist-recommended personality tests which continue to dominate the world of personal assessment today, including the Rorschach inkblot test and Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) of the projective test variety and the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), and a plethora of tests based upon Big Five personality traits (the tests are referred to as the Five Factor Model of personality) which belong to the self-report inventory category.

I have taken many personality tests over the years due to parental and psychologist suggestion that I have anxiety disorders and/or depression. The jury is still out on that diagnostic verdict, but I’ve definitely completed an MBTI or two, and a flood of Five Factor Model tests.

With the MBTI tests, which are essentially questionnaires attempting to couch you in terms of one of 16 psychological types through a four-letter abbreviation (the ideal being ESTJ: extraversion, sensing, thinking, judgment and the problematic INFP: introversion, intuition, feeling, perception), I always got the less than ideal option.

The Big Five Model is somewhat similar in that you are defined as open or cautious, conscientious or impulsive, extraverted or introverted, agreeable or antagonistic, and emotionally stable or neurotic. Unfortunately, my self-defined winning personality includes all the negative aspects of this Five Factor Model as well.

Regardless of personal experience, it is obvious that I am not the only person who’s taken more than a few personality tests in my time. It has become a literal phenomenon online and, more recently, websites such as Buzzfeed and Zimbio have banked off the combination of interest in pop-culture and personality with their fetching barrage of new quizzes. But why is this? Why are humans so incredibly intent on defining themselves in terms of what a personality test can provide?

“The scientific field is fascinated about defining personality because it is a more reliable definition of who we are as individuals, not as a species,” said Briscoe. “After all, even though identical twins have 100 percent of their DNA in common and look very similar, it is their demeanor and personality that define them.”

I believe the entirely human predisposition to need to box and clump complicated phenomena into an understandable, workable, and emotionally tangible term is behind this century-long fascination with personality tests. After all, we tend to be incredibly fearful of anything and everything we cannot put a name to.

It seems as if the terror of the unknown creeps its way into every facet of our lives, even our own personalities.

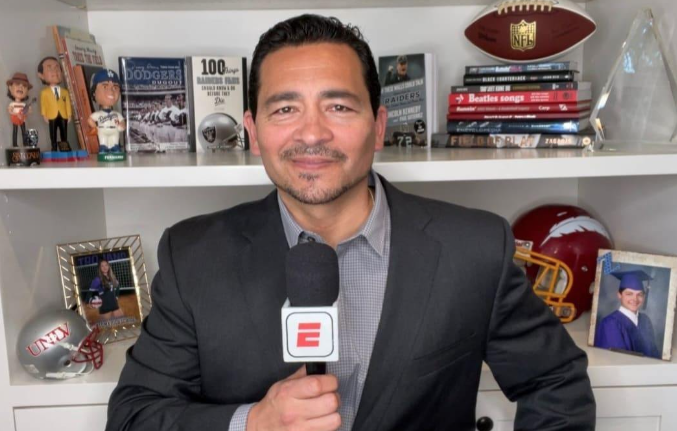

![[Both photos courtesy of sonoma.edu]

Ming-Ting Mike Lee stepped in as the new SSU president following Sakakis resignation in July 2022](https://sonomastatestar.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/CC4520AB-22A7-41B2-9F6F-2A2D5F76A28C-1200x1200.jpeg)