Black lives don’t matter, and this is because there’s no such thing as a black life. The rhetoric created as a reaction to recent fatal altercations between police officers and unarmed African-American men are encompassed by phrases such as #BlackLivesMatter, #ICan’tBreathe and #AllLivesMatter.

Although truthful and far-reaching, they barely begin to swim to the essence of prejudice against African-Americans.

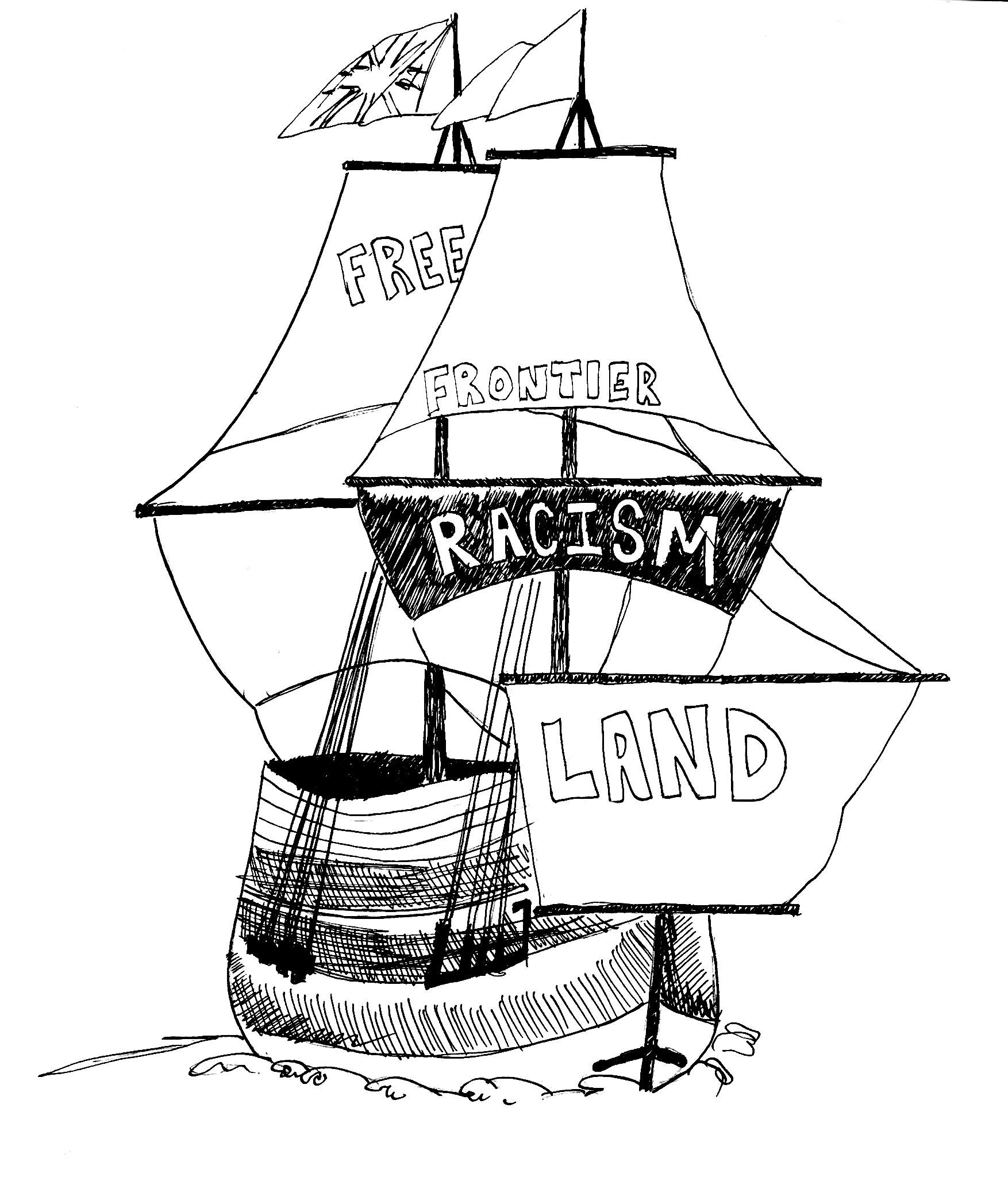

Even though any type of prejudice is sensitive to write, speak and protest about, it’s important the history and its residue in contemporary times be thoroughly understood. To dive right in, one must first be joined by the keen eyes of French psychiatrist and author Frantz Fanon.

His analysis on colonial psychology and more specifically, psychopathology, is important to understand if one is to even catch a glimpse of the nature of prejudice.

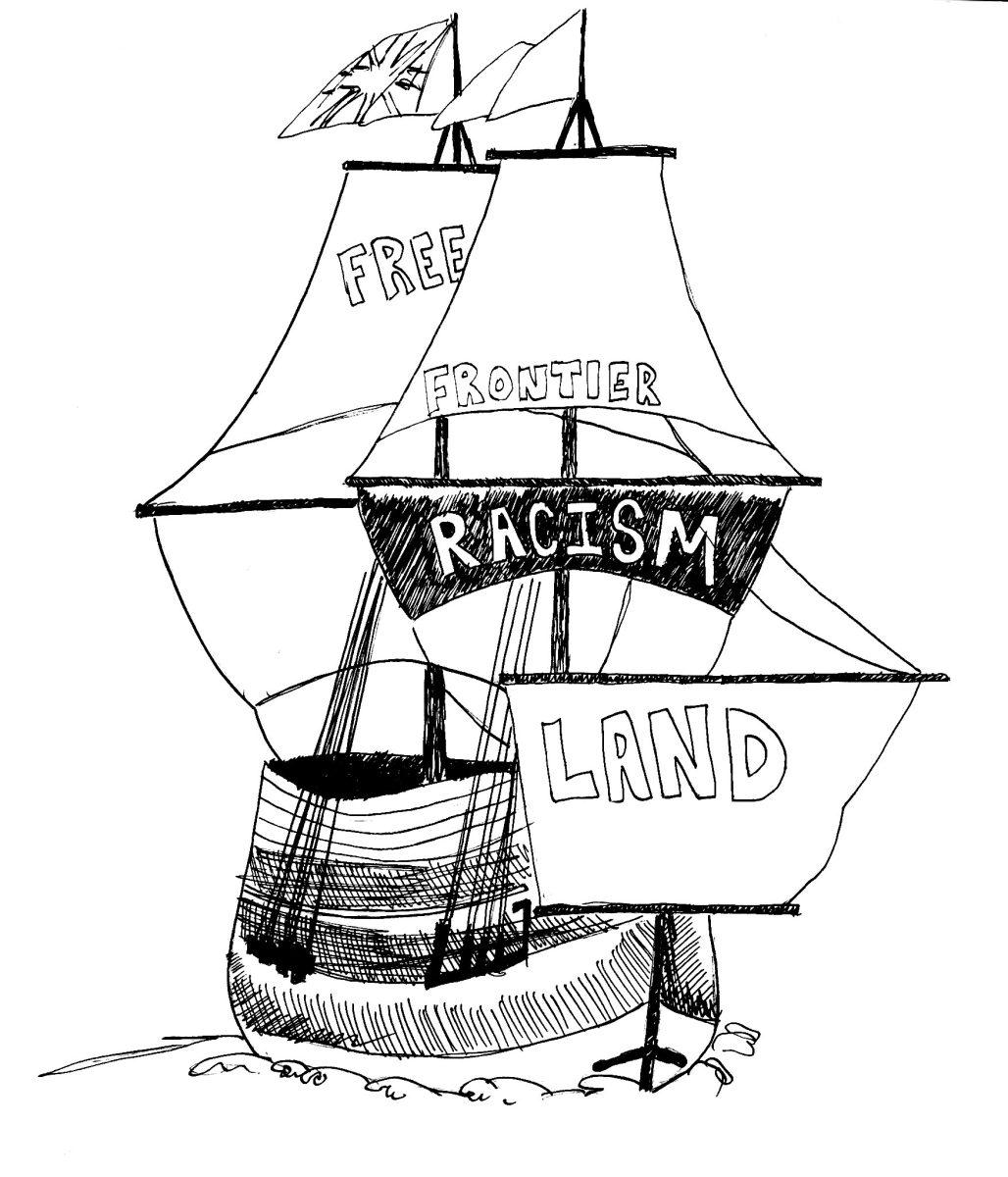

Fanon’s analysis in “Black Skin, White Masks” or “Peau Noir, Masques Blancs” is a helpful guide to swim with due to the way he breaks racism and colonialism down to its central parts. In addition, the way African-American individuals are treated in today’s society is arguably similar to how they were treated during the colonial era.

The contemporary situation is subtle at its best and utterly fatal at its worst. The black male isn’t castrated for sleeping with a white female in today’s world or lynched for similar deviant behavior.

He is rather treated fairly and humanely as in the case of Albert Woodfox who spent more than 40 years in solitary confinement in Louisiana despite there being no physical evidence connecting him to a crime in 1972.

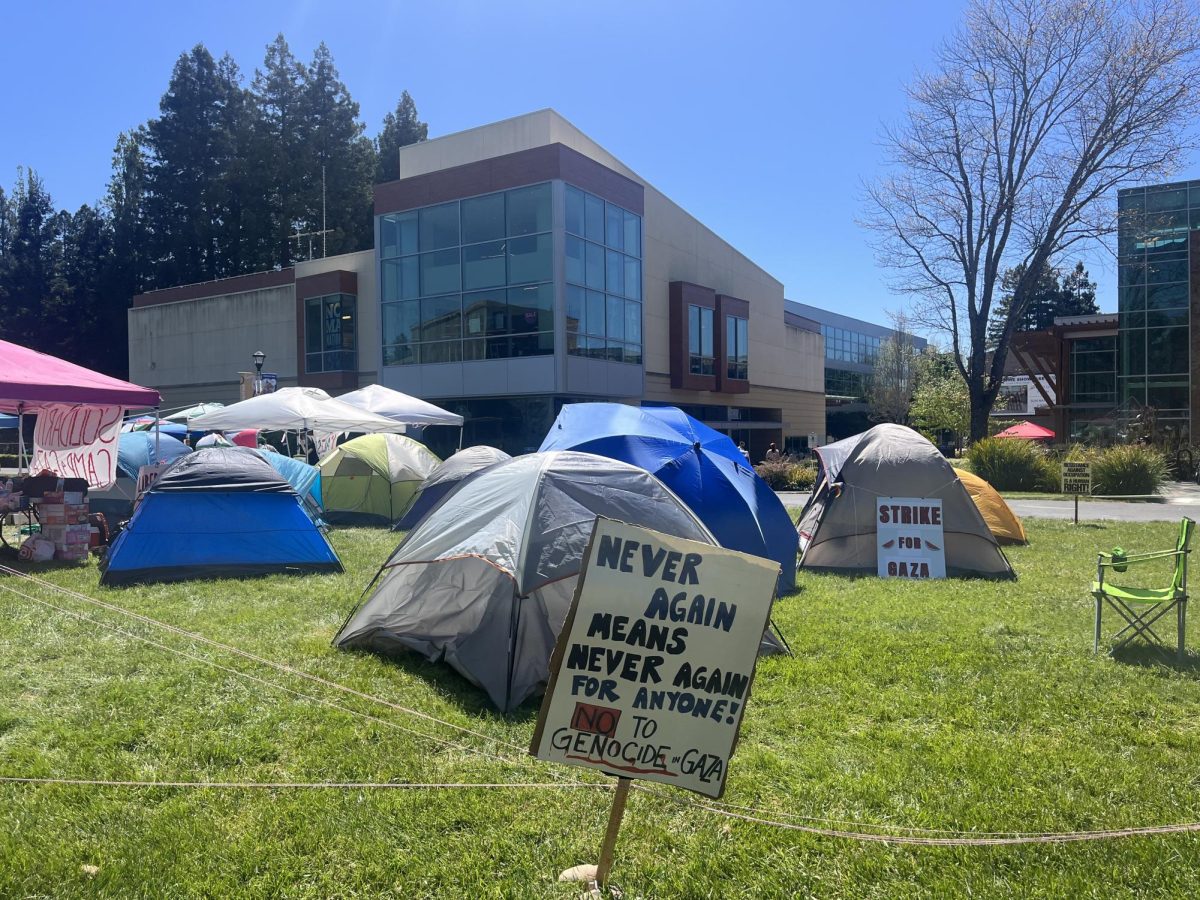

A subtle example includes a situation last year where a group of peers in Black Scholars United from Sonoma State University and Santa Rosa Junior College went bowling and were allegedly verbally abused and told “to go back to Africa” for “perpetuating the stereotype.”

The list goes on with the recent cases in Ferguson, Mo., and Staten Island, N.Y. where Eric Garner pleaded he couldn’t breathe.

As Fanon writes, “But the black man is attacked in his corporeality. It is his tangible personality that is lynched. It is his actual being that is dangerous.”

As deep as one is within the ocean of prejudice by now, he or she must keep swimming while solely focusing on the black male.

From Fanon’s existential and psychoanalytic perspective he (the black male) and the concept of projection are important.

The two main forces of sex and aggression are in play here and the black male is the subject of the projection. The other, whoever it may be, projects deeply held sexual desires, tensions and shadow aspects onto the black male.

Unconsciously, the black male is the shadow self. In turn, the black male becomes what Fanon labels a “biological danger.” Now take this situation and turn it into an obsession, and society reaches the boundary of the neurotic as well as a complex situation.

One is now in the zone of no return when it comes to prejudice. Things have gone too far. By now it’s clear there is no such thing as a black life, after having moved away from truthful rhetoric to uncomfortable psychoanalytic nuances.

As Fanon and Jean-Paul Sartre would say of this whole experience,“Nausea.”

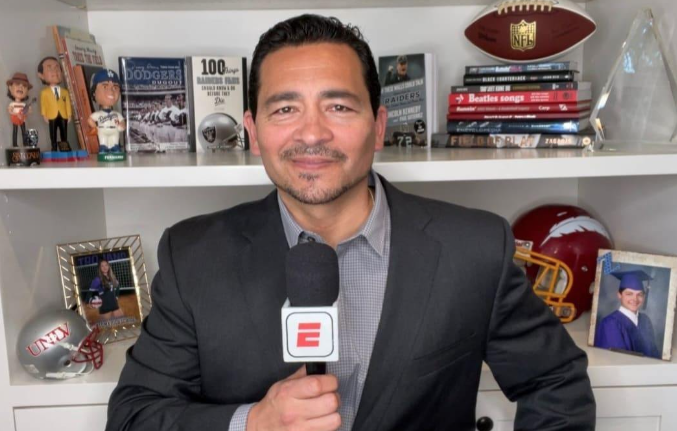

![[Both photos courtesy of sonoma.edu]

Ming-Ting Mike Lee stepped in as the new SSU president following Sakakis resignation in July 2022](https://sonomastatestar.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/CC4520AB-22A7-41B2-9F6F-2A2D5F76A28C-1200x1200.jpeg)