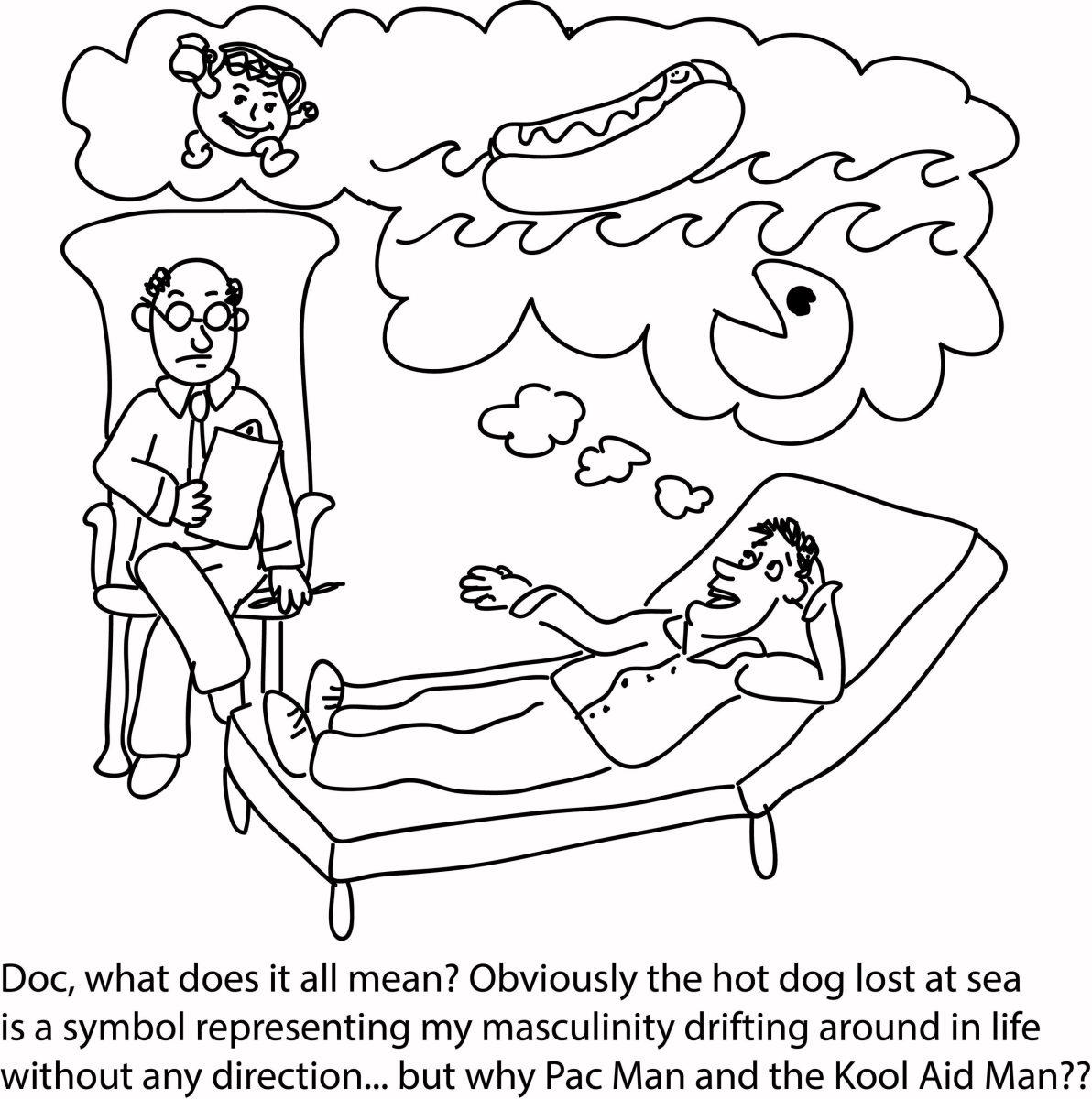

Whether you are falling, flying, running or observing an odd situation, dreams are arguably the most complex, and sometimes terrifying, experiences you can have.

They usually happen after transitioning from the deepest stage of sleep, where you are essentially paralyzed, to the last stage known as the rapid eye movement or REM.

Dreams offer everyone a chance to connect to their deepest self as well as perpetuate spiritual and psychic growth.

Further, journaling the majority of my dreams and learning about them from a psychological perspective has added a few skills in my toolkit.

Such skills include understanding how to seed a dream, lucid dream and extract meaning from any dream. Even though it sounds as if I am promoting the blockbuster movie “Inception,” all of these aspects of working with dreams are researched.

University of Chicago psychology professor Eugene Gendlin is well-known for his work with dreams as well as the “focusing” method, which he curated using work from famed psychologists such as Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung and Friedrich Perls.

With this method, one takes a dream and focuses on any given aspect while waiting for what he calls “a felt sense.” This butterfly-like feeling quite literally bursts open in your gut and, through various means, can help one grow toward a fuller and wholesome life experience.

As Gendlin writes in “Let Your Body Interpret Your Dreams,” “Growth feels expansive, forward-moving body energy. Comfort feels stuffy, boring after a while, limiting. Perhaps it is easier but it also has a sense of loss, giving up, giving in.”

Focusing is a personal and fun journey that I can attest to have helped me develop emotionally and mentally through a challenging period in my life. By journaling and relating my dreams to what happens in my life, I have developed an appreciation for uncertainty and embraced coincidences.

In partial contrast to the psychological aspect of dreams, Tibetan Buddhism also touches on similar aspects of growth, but from a spiritual perspective.

Author and Buddhist practitioner Sogyal Rinpoche discusses the similarities of dreams to a transitional state more commonly known in Tibetan language as a bardo.

In “The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying,” when you dream, you are in a state similar to the “karmic bardo,” in where you are clairvoyant, mentally mobile and possess a dream body to experience the dream world in.

As a yoga practitioner, Rinpoche’s description of this state resonates with me even though noticing it requires a certain level of awareness.

Once a mind is calm enough to observe a transition or state, the dream world becomes easier to navigate and learn from.

Recently I have noticed dreams are no longer happening to me due to the awareness of my active participation within the dream world.

In other words, I control aspects of my dream world, which is commonly known as lucid dreaming. It takes time to lucid dream and anyone can do it with enough practice. Apart from being fun, being aware within a dream can teach you lot about yourself in similar fashion to Gendlin’s approach.

So far I have noticed when you stare at people while lucid dreaming, or try to interact with them in a forceful way, they usually walk away or get distressed by the fact that you are aware of them. I have also learned and verified the source of all nightmares is excessive anxiety.

The meaning I have extracted from all of my dream experiences is that life is continuously mysterious.

There’s no longer a need for me to struggle with controlling what happens in my life and reacting to when things don’t go as planned. In essence, dreams offer a great lesson in letting go, which we can all benefit from.

![[Both photos courtesy of sonoma.edu]

Ming-Ting Mike Lee stepped in as the new SSU president following Sakakis resignation in July 2022](https://sonomastatestar.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/CC4520AB-22A7-41B2-9F6F-2A2D5F76A28C-1200x1200.jpeg)