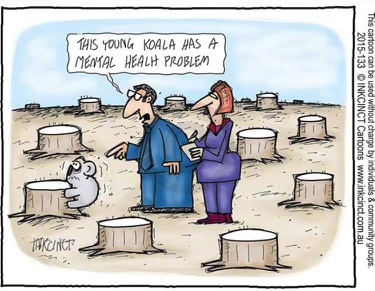

Health care workers across the world are risking their lives to protect their communities from the novel COVID-19 virus, but their noble work is putting their psychological health in great jeopardy. Not only are they suffering from the anxiety of caring for sick patients–while facing a dire lack of personal protective equipment and rapidly changing hospital protocols–but they are separating themselves from their families and loved ones for weeks on end to avoid the spread of the virus. Health care workers are sacrificing their lives for the well-being of others; they deserve more protection and resources for their mental well-being.

A recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association shed light on the shockingly large number of health care workers who are experiencing high rates of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and PTSD symptoms. The study examined the mental health outcomes of 1,257 health care workers attending to COVID-19 patients in 34 hospitals in China. Half of the workers reported experiencing symptoms of depression, 45% reported anxiety, 34% said they were having trouble sleeping, and over 71% were experiencing symptoms of psychological distress from the effects of the virus. If essential workers in our community are suffering, it is necessary that psychological support or interventions are provided. Not only do they deserve the help, considering that they are risking their lives and mental health for us, but also because we need our frontline workers to be strong, determined, and healthy in order to tame and hopefully at some point, end the pandemic.

The study also notes that during the 2003 SARS outbreak, health care workers feared they would infect their family or friends and felt stigmatized because they were in close contact with sick patients. They experienced significant long-term stress from their work during the outbreak, and the COVID-19 pandemic is likely causing health care workers similar stress.

During this pandemic, health care workers are also dealing with the stress of not having enough resources, such as ventilators and personal protective gear. Compounded with the rising number of deaths and sheer exhaustion from working extremely long shifts, health care workers are facing a second crisis. “I’m one step behind on crucial information, lack essential equipment, and drowning in community panic,” wrote Laura Danso, a family medicine physician assistant from Colorado, in a Quartz article. “People look to me daily to provide some measure of reassurance. I have little to offer.”

She writes about how the official recommendations from the Center for Disease Control and her bosses change every few hours, along with her and her colleagues often receiving conflicting information from them. Additionally, there’s a shortage of masks, so they are supposed to use one surgical mask a day, regardless of the obvious risk of contamination from contact with ill patients. Danso shared how frustrating and frightening this crisis is for health care workers like herself.

Interventions to promote mental wellbeing in health care workers exposed to COVID-19 need to be immediately implemented. During the SARS outbreak, stress appraisal and coping framework, as well as principles of psychological first aid were recommended by the American Psychological Association. Implementing these same services would likely benefit the mental well-being of our frontline health care workers now.

Protecting health care workers’ mental well-being is an important component of addressing the COVID-19 pandemic. More support and resources are desperately needed for those risking their lives and psychological health to fight the virus. Unless we begin to take action, the mental health crisis among health care workers is likely going to one of the most severe, long-term effects of this pandemic.

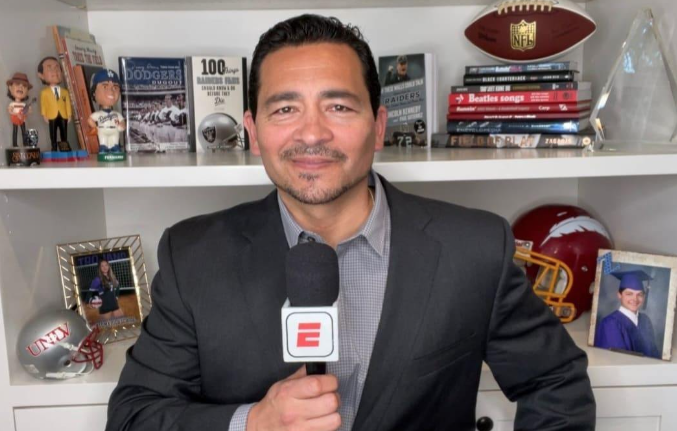

![[Both photos courtesy of sonoma.edu]

Ming-Ting Mike Lee stepped in as the new SSU president following Sakakis resignation in July 2022](https://sonomastatestar.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/CC4520AB-22A7-41B2-9F6F-2A2D5F76A28C-1200x1200.jpeg)