Sonoma County: known for butter and eggs, American Graffitti, wine, and now – gambling?

Actually, it’s a little bit more than that. At least, that’s the idea behind the $820 million Graton Resort and Casino, owned by the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria.

Scheduled to open to the public on Nov. 5, Tribal Chairman Greg Sarris and General Manager Joe Hasson opened the casino’s doors for the first time last Wednesday, granting local media a sneak peek of Sonoma County’s newest attraction.

“I never saw it as just a gaming facility, but as a destination,” said Sarris, emphasizing that the 10-year project is unlike any casino in the country.

The 340,000 square foot facility’s design and recreational elements are carefully constructed, such as its intricate woodwork and marble fixtures that can even be found in the bathroom. The smells of paint and wood filled the air as Sarris and Hasson walked the group around the building, explaining the significance of its design elements. A terrazzo-tiled walkway, for example, surrounds the exterior of the gaming floor, which Hasson referred to as “the yellow brick road.”

There a few elements that Sarris and Hasson believe to be groundbreaking for a casino, such as a vertical, up-the-wall ice machine with four varieties of ice, and a sky bar featuring – lo and behold – outside light.

“There’s no other casino in America with open light,” said Sarris. “It was important for the facility not to be oppressive.” Sarris also said there would be clocks within the casino so people knew what time it was, a hard-to-find quality in most North American casinos due to the popular strategy of customer confinement.

The casino features 14 different dining options, many of which are local to Sonoma County.

“I grew up on Mexican food, and I know this is the best,” said Sarris, referring to “La Fondita,” a local taco truck-turned restaurant in the casino’s 500-person food court. Dining options also include Boathouse Asian Bistro, The Habit Burger Grill, M.Y. China and Starbucks. There will be outside entrances to the restaurants to accommodate minors.

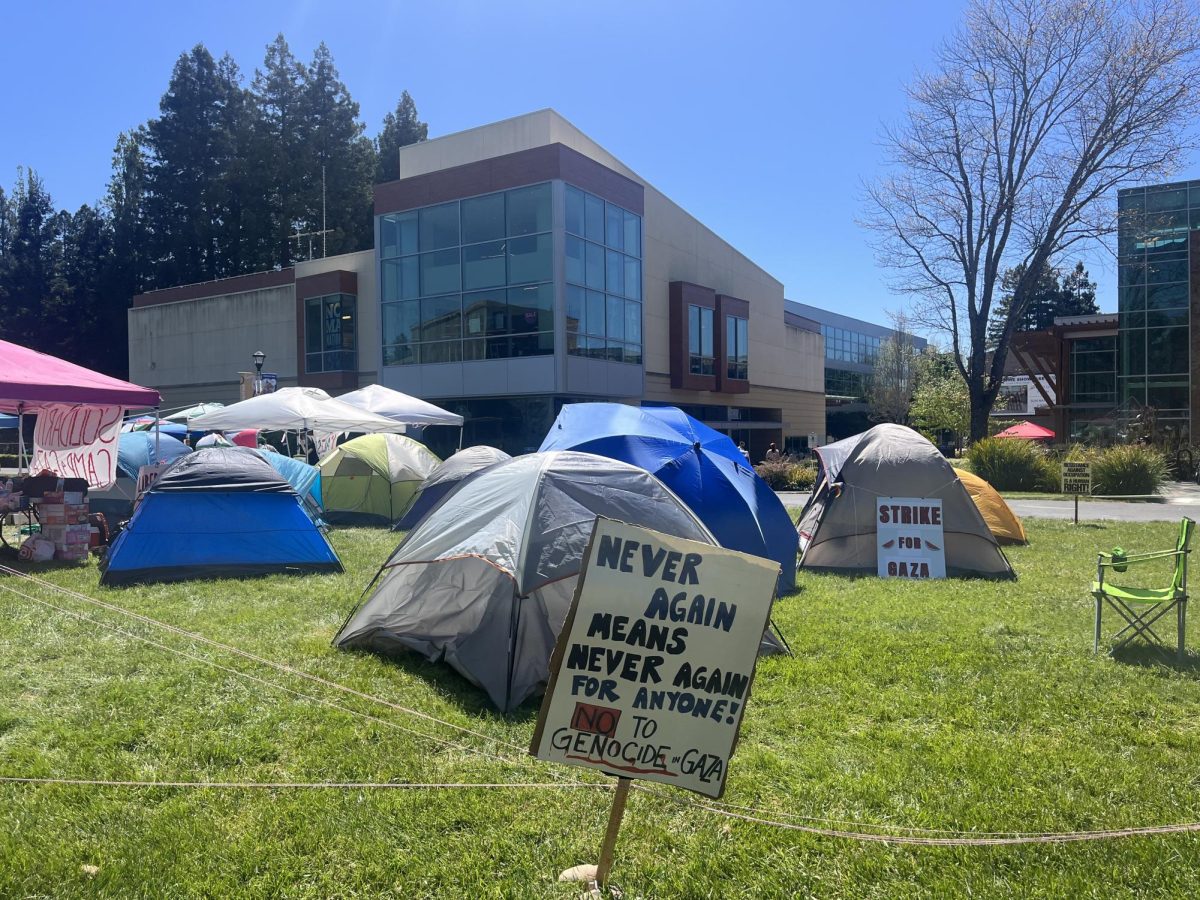

Sarris and the casino have been under Sonoma County’s spotlight for the past 10 years, bringing both excitement for and opposition against the $820 million project.

Many protesters continue to fight against the casino, arguing that gambling, traffic and negative environmental impacts are the last things Rohnert Park needs.

Stop Graton Casino, an opposition movement started by SSU Alumna Sabrina Hrabe, is adamantly fighting to keep Graton Casino’s doors shut.

Members are concerned the business will inspire other Indian casinos to start up around Sonoma County, which they fear will ruin the area.

The group is questioning the legality of the tribe’s right to the land on which the casino is being built, and has the support of many community members – including several Sonoma State students.

“It doesn’t matter if the casino opens, because a court order can shut it down,” said Hrabe.

Supporters, on the other hand, applaud Sarris’ efforts and actions to keep the community satisfied by hiring 2,000 employees, channeling local resources and the recent passage of a Memorandum of Understanding that designates portions of the tribe’s income to the city, including the Cotati-Rohnert Park Unified School District.

Having predicted $251 million in income over the next 20 years, Sarris said the casino will host 2,000 full time jobs, 1,250 of which have already been filled.

There are currently 700 construction workers, and over 1,500 California based companies have been utilized in the casino’s construction.

Media Representative Brianna Dunn said there is no way for Graton to tell how many employees are associated with Sonoma State.

Station Casinos, a Las Vegas-based gaming and hospitality firm, has and will be responsible for the development and management of Graton Resort.

“I’m glad to be alive, and to have delivered all that I promised,” said Sarris. “There will be so many employees and benefits to the community.”

![[Both photos courtesy of sonoma.edu]

Ming-Ting Mike Lee stepped in as the new SSU president following Sakakis resignation in July 2022](https://sonomastatestar.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/CC4520AB-22A7-41B2-9F6F-2A2D5F76A28C-1200x1200.jpeg)