Since the birth of movie theatres in 1905 with the Nickelodeon in Pittsburgh, going to the movies has morphed into a classic American pastime. Where and the way we watch movies has dramatically evolved over the years. In the 1930s, it started with installation of the first drive-in theatre. Fast forward decades later and movie theatres now have state-of-the-art sound systems, high-definition wide screens and, at some locations, waiters who serve you gourmet food. Time has shown that the movie theater experience has and continues to thrive, despite the ever-growing popularity of streaming sites such as Netflix and Hulu.

Despite all these superficial advancements, there is one question that seems to go unanswered; what about evolving the movie experience for those that have sight or hearing impairments?

Nyle DiMarco, deaf activist and model, voiced his complaints with his viewing experience for the recently released film “Black Panther,” tweeting, “It was awful. Kept skipping lines. The difference of focus while switching gave me a headache and I kept missing important scenes. AMC Theatres made me feel SO disabled.”

According to the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, about 37.5 million people ages 18 and over across the United States report varying levels of hearing troubles. Do these millions of people face similar difficulties like DiMarco and would prefer the comfort of their own home than a theater?

This tweet fueled a much-needed discussion about acknowledging the difficulties of those with varying hearing impairments face when simply trying to enjoy a movie. In order to make their experience as comfortable as possible, mainstream movie theatres typically offer caption options; either open or closed.

Generally, the viewer can willingly turn closed captions on or off; as seen on Netflix’s viewing settings. For movie viewing purposes, this normally comes with a closed caption machine, the same one DiMarco complains about in his tweet. AMC Theatres calls these machines CaptiView and, despite what DiMarco and others have said about its difficulties, claims the device is overall easy to adjust to one’s viewing comfort.

Yes, theater chains designed those closed captioned machines to aid the viewer and are better than not having anything at all. But they indirectly make those that are deaf or have other hearing impairments feel different or as burdens, when they shouldn’t.

Open captions are always visible on screen, making a separate caption machine unnecessary. Ideally, this option would be the best choice for movie-goers with hearing impairments. Unfortunately, not many theaters offer this.

Popular movie theatre chains such as Regal Cinemas and Reading Theatres offer their guests assistive listening devices. According to the National Association of the Deaf, they have designed these devices to amplify and transmit sounds directly to the ear while also improving “the speech to noise ratio” for those with mild to severe deafness.

In order to depict how blind people enjoy the movies, the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences launched a mini documentary series in 2014. Melissa Hudson, one of the interviewees, said, “The way I watch movies is just like everybody else,” but she tries to find theatres that offer a descriptive video service.

Being able to watch and go to the movies is a huge cultural component in our society, so let’s not push any group of people out of the conversation just because they’re different than us.

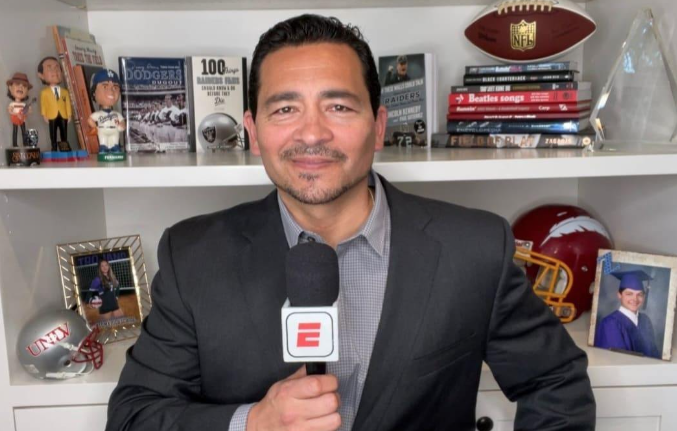

![[Both photos courtesy of sonoma.edu]

Ming-Ting Mike Lee stepped in as the new SSU president following Sakakis resignation in July 2022](https://sonomastatestar.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/CC4520AB-22A7-41B2-9F6F-2A2D5F76A28C-1200x1200.jpeg)