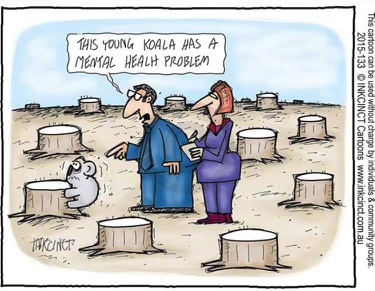

When the California State University system faces budget cuts, educators pay the price with their jobs. The California State University system reported to have a majority of part-time faculty during the 2013-14 academic year. This shift of instructors has serious ramifications both in and out of the classroom, and holds several implications in regard to the institution of higher education in California.

The first of these is the concern of accessibility. California state universities are supposed to be accessible institutions of higher education, but with more part-time faculty than full-time professors, they may not be so accessible after all.

“Students have a far less likely chance of gaining access to part-time teachers outside of class simply because these teachers only spend part of their day here,” said professor John. P. Sullins, chair of the philosophy department. “In many cases, they may teach at other institutions or have other part-time jobs they work at in addition to what they do for us here.”

This brings up the concern regarding the quality of education offered at the California State University. Like students, California State University instructors are not considered to have full-time status unless they carry a workload of at least 12 units.

However, when part-time professors must commute several times a week between, say San Francisco State University and Sonoma State University, transport becomes another element of the position for which faculty members must account.

With this in mind, one must wonder if an instructor takes on too much just to pay their bills; all projects will suffer under the strain.

Additionally, it is important to recognize that “part time” and “full time” are not the only categories in which teaching professionals fall. Within full-time instructor positions are tenure track and non-tenure track professors.

Professors may not be on the tenure track, but still maintain a certain amount of job security in their workload and contract. However, without the near absolute security tenure status offers, no instructor can really feel safe in their job.

“They have to watch what they say in the classroom or in public since they can be fired much more easily, or at least just not hired again next semester,” said Sullins.

The idea that one can be so easily replaced is discouraging to those who hope to enter the professional field of teaching.

“Since I was little I have wanted to go into teaching,” said Claire Varner, a fourth-year Hutchins student. “There’s always been that fear that I won’t have a job. You know, they’re cutting back on teaching.”

This kind of dispose-and-replace employment system is less expensive for universities to maintain. This hiring model is problematic because it’s based on people who will not be there in the long run. If students form a good rapport with a professor and development skills in a given subject, they face the possibility of not being able to contact that professor for a recommendation because they have moved to a different institution.

Hiring professors on a semester-by-semester basis bears a striking resemblance to corporate patterns of seasonal employment.

But this is not a corporation, it’s not a business; it’s a place of higher learning for future contributors of society. The cheapening of accomplished teaching professions inevitably impacts the education they provide.

“It makes me concerned about the commitment that the system is demonstrating toward the diverse student body that we have at the CSU,” said Lillian Taiz, professor of history at CSU Los Angeles, and president of the California Faculty Association. “Maybe they can get away with it, but I think when you do things on the cheap in an institution of higher education, somebody’s going to pay the price.”

With cuts in education funding causing the California State University to save money by hiring faculty on a part-time basis, those left to pay the price are the educators, and ultimately, the students they teach.

![[Both photos courtesy of sonoma.edu]

Ming-Ting Mike Lee stepped in as the new SSU president following Sakakis resignation in July 2022](https://sonomastatestar.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/CC4520AB-22A7-41B2-9F6F-2A2D5F76A28C-1200x1200.jpeg)