There is an ancient Native American prophecy that speaks of a great black snake that will one day run through all the valleys and rivers, desecrating life in its path. From east to west, tribal elders have warned for generations this monster was coming. And today it seems it is finally upon us.

Fifteen hundred miles away, just outside the Standing Rock Sioux reservation in North Dakota, lies more than 300 native tribes gathered to protect water from a 1,172-mile-long oil pipeline that, when completed, will cross both the Missouri and Mississippi rivers.

No effort has received as much unanimity among Native tribes in the history of American colonialism. Since April, an estimated 50,000 people, native and non-native, have made their way to and from the Oceti Sakowin encampment on the shores of Sacred Stone off Highway 1806.

Energy Transfer Partners, the Texas-based company that’s building the Dakota Access pipeline, contends the project will create thousands of jobs and help America break its dependence on oil from the Middle East.

So on Oct. 19, I decided I would pack up and drive halfway across the country to witness David face Goliath for myself. No holds barred. I didn’t know what I was expecting to see or learn from any of this, but what I experienced soon became one of the most horrific events of my life during which I was threatened with batons, rubber bullets and pepper spray. I witnessed innocent people, including credentialed journalists, chased by private security on ATV’s across rivers and hills, and elderly men and women in prayer, handcuffed and maced. The great black snake had indeed struck. These are my accounts from inside the belly of the beast. Following a 30-hour drive, I arrived at the Standing Rock Sioux reservation just as the sun was mounting the hills to the east. I told the men and women at the front gate that I was a reporter from my college paper. Without pledging any kind of loyalty to their cause, I was welcomed in with smiles and blessings.

Given their placement, I took these individuals to be camp security. They pointed out two things to me: The first was where I needed to go in the morning for a press pass. The second was a great big sign that said “We are unarmed.” As I read it aloud, one of the men replied, “and we ask that you are the same.” An hour or so passed. The sun rise was accompanied by a morning prayer lead by elders at the main fire.

Before long, I was up in a tent with journalists from across the country. There were two men there from Slate Magazine who came and left by midday.

In fact, many whom I spoke with did not plan a long trip in fear of being arrested from what they heard and saw on the news. Afterwards, I was credentialed and put through a security debriefing on what to expect on the front lines of the protest. I was told I would be targeted. I was told I could be charged on felony counts and that my property might not make it back in one piece. Don’t get me wrong, this was a friendly warning, not a scare tactic. Still, it didn’t take long before I understood that I was a candidate for pepper spray solely based on what side of the line I was reporting from. Less than two hours later, I found myself in the bed of a full pickup truck on the way to sacred burial grounds for my first experience on the front lines.

I was told there was already a barricade set up along Highway 1806 awaiting the arrival of protesters. On the way, our caravan drove past a U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs officer who surprisingly held up his fist in solidarity with the yips and whoops coming from our mechanical chariot.

After about five miles, we hopped out and gathered with the rest of the group for a pre-march prayer down to the police blockade.

Precise instructions were given on how this march would unfold.

“We’re going to go down there. We’re going to put this flag in the ground. We are going to pray. And we are going to leave,” said one young man, who couldn’t have been more than 20 years old, and appeared to be in command of approximately 70 people.

A half hour of prayer, song and dance in the face of riot police was enough for the day. With no arrests, we made our way back to camp for the evening.

I overheard a man in a traditional dress say how the following morning would be a big day, and it seemed everyone in camp was under the same impression.

On my way from the main fire, I came across what I later learned was a school for children. In an interview, a woman explained to me how they left their reservation four months prior to join their people in protecting their sacred lands and waters.

She reassured me that the decision wasn’t an easy one. Being a mother of a 6-year-old and a 9-year-old child, she said she understood the importance of keeping her kids in school.

“That is why this community is so important to our success. It makes it so we can stay here and fight the black snake as one,” she said.

I wandered through a few more camps before heading back to my tent for the night. It was 8 p.m. and the temperature was in a rapid decline so I thought I’d build a fire. I grabbed my ax and began to break down a fallen tree nearby. It couldn’t have been more than a minute and the group camped next to me came over to offer their assistance. Before you knew it there was seven of us huddled by the fire sharing stories.

They were a mixed group of Comanche and Kiowa Apache that hailed from Oklahoma. For them, this was either their fifth or sixth time traveling out to stand with their Standing Rock Sioux brothers and sisters. Jeremy Tahhahwah, a full blooded Comanche and Kiowa Apache, reminded me of how his tribe nearly killed off all the other native tribes due to their ruthlessness, and how Comanche solidarity with the Standing Rock Sioux meant something powerful is at work.

“We all know of this black snake. We Comanche will continue to fight for our land, but this here is something far more sacred. We need water. Water is life and we need to protect it,” said Tahhahwah.

At 5:30 a.m. the next morning came the call to duty.

“Wake up brothers and sisters. It is time to join us in prayer. Wake up brothers and sisters.”

I don’t think I’ve ever moved that fast that early in the morning. This time in my rental car, I made my way across camp and got in line with those headed out for the daily action. There were nearly 500 people amassing at the exit to send off the water protectors in prayer.

After a two-mile drive north cars began to pull off the road and park. I recognized this place. This was the site I saw online where private security used attack dogs to restrain water protectors a month earlier. My stomach was in knots. But using the dark as camouflage they began to march toward those construction sites once again. Unsure of what was about to happen, I followed.

From this point on my faith in this country changed forever.

I did my best to stay at the front of the group capturing every significant moment I could. It was hard. There were more than 350 people in prayer. All nationalities and religions. Prayers were made to the Grandmother and prayers to the Holy Spirit. There were tears of joy and tears of fear for what may lay ahead. In one moment, everyone’s cell phone rang with an emergency alert warning, and you could feel the anxiety creeping into the voices of the protectors.

“They blocked off the highway behind us,” a young woman shouted. “It says to avoid the area at all costs due to extreme rioting.”

Those who brought it began to light up sage and share it with those who were quivering. Sage is used in Native American rituals as a way to cleanse yourself of bad energy and omens.

As we approached the construction site, we were met by a force unlike anything I had seen outside of a video game. Over 50 officers, two heavily armored riot vehicles, Knightsbridge Risk Management private security on ATV’s, and SWAT were waiting for protestors.

It was a daunting sight. So, instead of marching directly towards the line of officers, water protectors did their best to literally take the road less traveled and access the construction site from the long way around.

Still in prayer, the majority of the group continued on, dedicated to spreading the officers thin and getting to the site. At the same time, I saw one man approach the initial police blockade.

Once the water protectors realized there was no hope of reaching the site without antagonizing police, they began to retreat back where we parted. In that moment, an officer came over the microphone and said, “We have identified you all. You are all under arrest for criminal trespassing. Stay where you are. If you leave you will be pursued.”

That’s when things got ugly. From our vantage point, we could see men, women and elders being grabbed from the crowd and body slammed to the ground. Mind you, everyone was locked in arms and still in prayer. You could hear police shouting “get the camera.” Out of about 20 journalists I saw go out with the group, all of five made it back. One man came back with a broken lens afer being tackled. One man came back without any shoes. One man could hardly see from the pepper spray in his face. We sat there and watched as one by one they arrested everyone who stood their ground. We watched them spray pepper clouds on the water protectors as if it was silly string at a party.

What moved me the most was the reaction from the crowd behind me. There was no malice. No hated. Anger, maybe, but sadness and solidarity with the movement was all I heard. “We love you.” “We respect you.” “We are here to defend your children as well as ours.” That’s it. These water protectors want anything but to incite violence.

As the police pushed us back to the highway, they picked off everyone they could from the back of the group. The slowest and the weakest; the 75-year-olds and up.

We did our best to keep the elders in the front, but it became impossible to save everyone. Riders on horseback came stampeding down the hills like a scene out of “Lord of the Rings” to grab whomever couldn’t move fast enough. At the end of the day, more than 140 protestors were arrested, including one of whom I met in camp and some I met that morning.

During the hours that followed, I never felt so low. My insides hurt. I never thought I would see police treat people in prayer the way they did. It made me realize something about the world we live in. It showed me the lengths big banks are willing to go to in order to make more money.

The next morning, I picked up my camp, said goodbye to my Comanche brothers and sisters and headed back to California. Now, I’m doing everything I can to help from here.

At this moment, there is a letter of solidarity bouncing around from department to department where professors are signing up to stand with Sanding Rock.

We are planning to attend the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors meeting this morning to ask for similar support.

For more information on how to join the movement please contact me at [email protected] or check out the Sonoma County Solidarity Facebook page @SonomaNoDAPL.

![[Both photos courtesy of sonoma.edu]

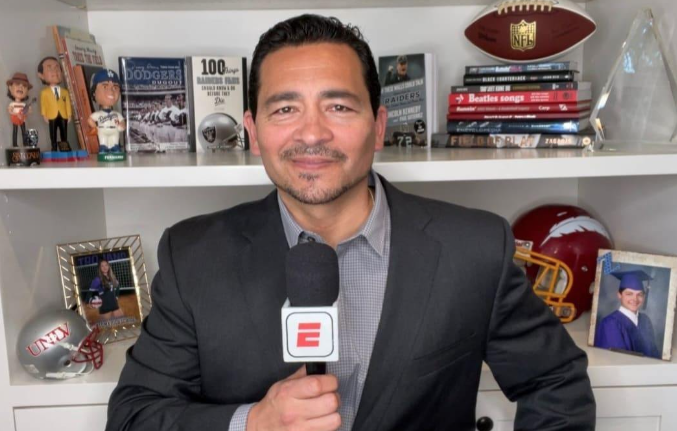

Ming-Ting Mike Lee stepped in as the new SSU president following Sakakis resignation in July 2022](https://sonomastatestar.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/CC4520AB-22A7-41B2-9F6F-2A2D5F76A28C-1200x1200.jpeg)