This week, the Native American Studies Department kicked off a new lecture series, titled Fire on the Land and in Our Lives. Starting off this lecture series, Tribal Chairman of the North Fork Mono tribe, Ron Goode, presented “The Heritage, Perspectives, and Practices of the North Fork Mono Tribe.”

The event opened with a land acknowledgement led by Amal Munayer, who is an advisor for the Educational Opportunity Program at SSU. This opener acknowledged the stolen land that Sonoma State was built on, as the ancestral homeland of the Coast Miwok and Pomo Tribes of Northern California. These tribes are now united as the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria.

Goode discussed an abundance of topics in relation to the North Fork Mono Tribe, focusing highly on cultural burning practices as part of land management, and tribal culture.

Casey Ditzhazy, SSU senior, attended the event as part of a class, stating that she “appreciated how we’ve been able to incorporate Indigenous voices into our courses and University culture.” Ditzhazy was also surprised by the high turnout of the event, around 70 people, and said “it’s cool that we can still have opportunities to do things like this during COVID-19.

One of the main themes of the event was cultural burning practices of the North Fork Mono Tribe. Cultural burnings are small area fires which are used by many Indigenous tribes, and guided by traditional ecological knowledge in order to help the forest to become more healthy, and help to combat the more severe effects of wildfires.

The North Fork Mono, among other Native tribes, believe that fire can be used as a tool and have seen the very real results of this belief in their homelands. To perform these cultural burning practices, members of the tribe determine whether or not a piece of land is essentially overdue for a fire. The land is then cleared of excess debris, tree limbs, and ground brush, and a small fire is started in the area, to cleanse the land.

Goode also discussed other cultural practices of the North Fork Mono Tribe, such as games played by the members of the Central Valley Native tribes. Some of these games include: archery, tree rag, buzz, and a bead guessing game.

The event concluded with a Q&A with Goode, and many students had questions to ask him. When Goode was asked about what he thought the benefits were of events such as this one, he said “There’s a lot of folks out there like me, who are doing wonderful things and have a lot of knowledge,” but added that Indigenous Peoples are too often exploited for this cultural knowledge when they choose to share it.

He added that in the past, his claims have often been compared to Western science, as a way of trying to “legitimize” traditional ecological knowledge, in the eyes of people who are unwilling to learn about it.

Goode believes this is why many Indigenous people can be “gun-shy” about sharing this type of knowledge, but he continues to do so because he wants people to try to understand what he thinks “the right way to do things is.” This event was a great way to kick off what is sure to be an interesting series about Native American perspectives on the fires that affect the lives of everyone in Northern California.

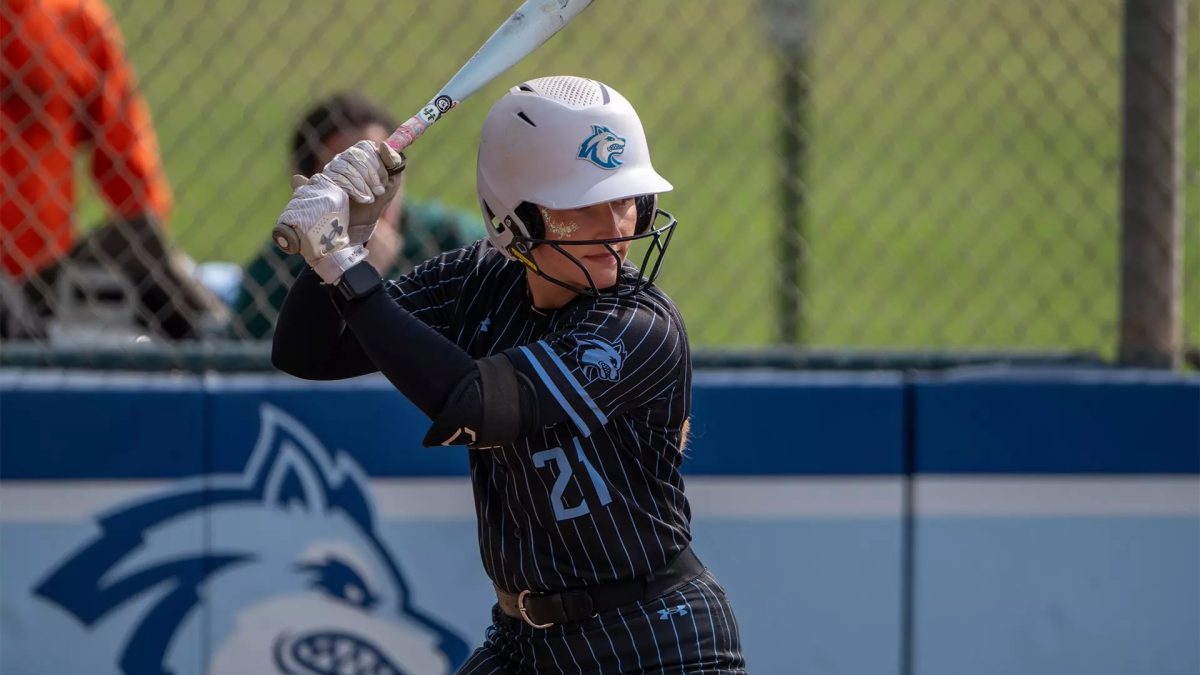

COURTESY // North Fork Rancheria

Ron Goode speaks to SSU about the North Fork Mono Tribe.