Columnist Matthew Koch

On April 25, 1980, it was a regular scorching afternoon in Houston, where the 70-year-old store clerk James McCarble was tending the register, alongside employee Edna Scott, just as he did every day in the past—only this time would be his last.

“Fill it up man, you’re being robbed!” yelled a Willie Albert Koonce, who had entered the courtesy booth, accompanied by Everette Anthony Pradia and Bobby James Moore, with a duffle bag and a loaded gun.

In a panic, Scott shouted that a robbery was taking place and dropped to floor, meanwhile McCarble, jumping to the left of Scott to get out of the way, was met by Moore brandishing a loaded shotgun aimed right for his face.

A gunshot sounded as McCarble fell to the floor—the three men making their escape by car.

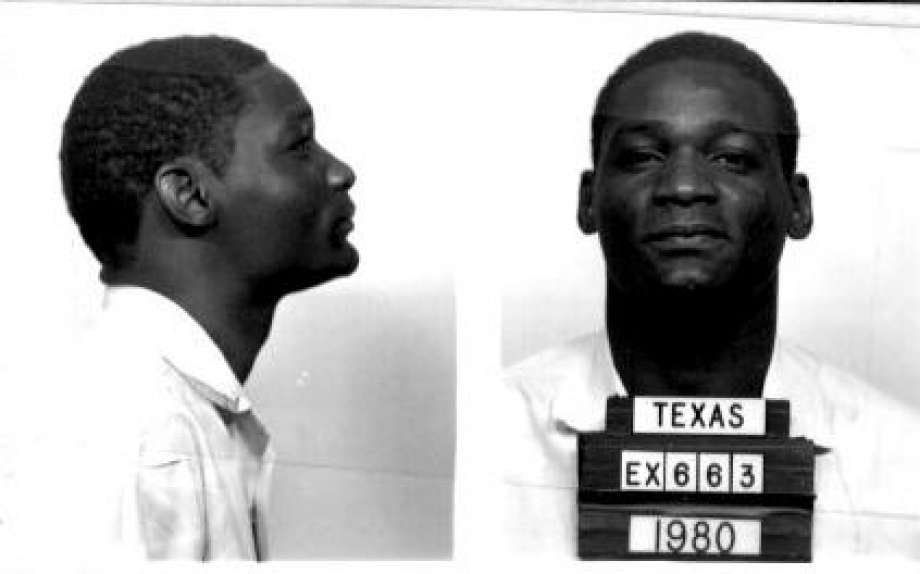

Jumping ahead 37 years later, Bobby James Moore was convicted of the 1980 murder of James McCarble and eligible for the death penalty, according to the lower circuit courts of Texas.

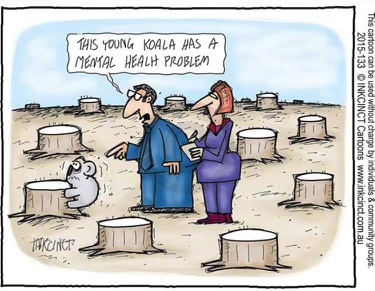

There’s only one issue in all this: Moore’s IQ score indicated that he had the mind of a 9 year old.

People clinically proven to have a mental disability, like Moore, should be exempt from the death penalty.

According to the UN Commission on Human Rights, all states that maintain the death penalty are urged “not to impose it on a person suffering from any form of mental disorder; not to execute any such person.”

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote the 5-3 opinion holding that the lower court that ruled against Moore had relied upon outdated standards, according to CNN. Ginsburg said the lower court’s conclusion that Moore’s IQ scores established that he is not intellectually disabled are “irreconcilable” with Supreme Court precedent.

While it’s good that the Supreme Court didn’t execute Moore, it’s shameful that it took so long to reach an understanding when all along he could have been helped rehabilitated with some sort of mental health services.

During the 1970s, Massachusetts prisons were like war zones. There was an epidemic of homicides, suicides, gang rapes and other acts of extreme violence. An investigation into the conditions of the prisons and its inmates determined that most of the violence was precipitated by untreated, undiagnosed mental illness, according to James Gilligan, director of mental health services for the prison system.

Gilligan, with a team of mental health professionals, were called on to direct a program setting up mental health clinics and psychiatric emergency rooms within the prisons. During his program emphasizing mental health treatment for inmates, homicides and suicides fell from an average of once a month to only eight during the 10 years his program was in place.

Judging by the dramatic decline in homicides after implementing mental health services, it’s obvious that Gilligan’s approach is far better than retribution by death.

In 2014, San Quentin is following suit under court pressure to improve psychiatric care for deeply disturbed death row inmates, according to the Los Angeles Times. The court-appointed monitor of mental health care in California’s prison system reported to judges that about three dozen men on death row are so mentally ill that they require inpatient care, with 24-hour nursing.

Mental Health America, a leading mental health group, estimates that 5 to 10 percent of all death row inmates suffer from a severe mental illness.

The sooner the courts, the prison systems and society as a whole addresses mental illness as the serious issue that it is, the sooner we can develop solutions.