STAR // Kayla E. Galloway

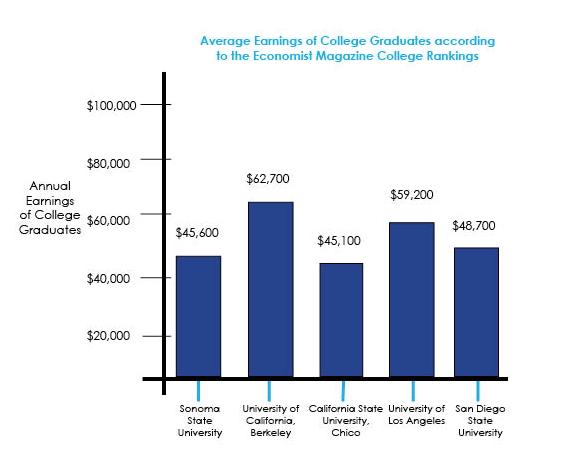

Students may already know that sources like U.S. News and World Report and College Board have been releasing college rankings for years, but recently The Economist”joined in with its first ever college ranking system; a list with a slightly different approach. Rather than ranking colleges based on graduates’ average salary, or the niceness of their dorms, The Economist ranked each college based on the economic value of its degree. Sonoma State University was ranked dead last among other California State Universities.

To determine a degree’s economic value, The Economist first calculated how much students should potentionally be making after graduating from a particular school.

For each college, they looked at their freshman class of 2001 and determined average SAT score, ratio of male to female, racial demographics, students’ majors, the size of the college, and the wealth of the state.

In addition, they accounted for the type of college; whether it was public or private, a liberal arts, engineering, or business school, and lastly, its religious affiliation, if any. According to the results from their formula, students who graduate with a degree from Sonoma State are estimated to earn an annual income of $48,462.

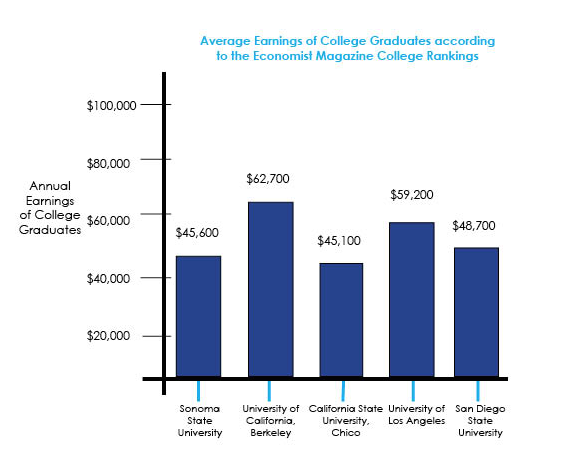

To determine the college’s ranking, “The Economist” compared this number to how much students actually made in 2011. On average, the freshman class of 2001 made $45,600 a year, $2,862 less than predicted, placing Sonoma State at 1,032 out of the 1,275 four-year colleges on the list.

This spurs the question: why?

Brandon Mercer, president of Associated Students, believes Sonoma State’s lackluster ranking may be due to its status as a liberal arts college.

“We invest in students to be well-rounded citizens when we send them out into California’s economy and so, it’s not just what you’ve learned in the classroom,” said Mercer. “It’s the leadership skills you’ve learned, it’s the interpersonal skills, and that’s something that we’re focused on. We’re focused on the holistic development of our students not just the dollar amount that they get offered when they walk out of our doors.”

According to Erik Dickson, Associated Students’ executive director, a liberal arts education at Sonoma State is still valuable.

“It’s that breadth of education, it’s that looking at all things from different perspectives, which is generally the value of a liberal arts education,” Dickson said. “The ability to get it at Sonoma State in a public institution, a public CSU, which also is an institution which has excellent programs in business, in sciences, in those sorts of places, gives you a little bit of a liberal arts approach with the opportunity to be a wine business student, or be a biology major, or be something that isn’t necessarily tied directly to liberal arts.”

Economics Professor Robert Eyler agrees with Mercer and Dickson that Sonoma State’s liberal arts focus draws more liberal arts majors who tend to make less money right out of college than mathematically based majors, like engineering. However, Eyler also attributes part of Sonoma State’s placement to the Bay Area’s high cost of living, which causes students to accumulate more debt.

Despite this, Eyler doesn’t think the value of a Sonoma State degree can be accurately measured from The Economist’s formula.

“To me, a better way of thinking about the worth of a degree is what does it do over your lifetime, because a lot of people will get a good job right out of the gate, engineering is a great example of this, but at a certain point, engineering will plateau, and the flexibility of an engineer from one job to another without another degree over time is somewhat limited,” Eyler said. “So a lot of the arguments that degrees are starting to become worthless are somewhat in the eye of the beholder. A lot of lawyers are English majors or philosophy majors because they leverage that bachelor’s degree to go to law school. You need to be a good writer, good logic: philosophy and English.”

Eyler thinks that a good way for Sonoma State to increase the economic value of its degree would be to become more of a pipeline for local, high-paying employers.

“When our majors come out, we should ask our students to do what makes them more marketable,” Eyler said. “If you knew in January that you were going to graduate in May, but there were three or four jobs lined up for you, and you had prepared for those jobs because when you were a sophomore because we told you what classes to take, you’ll have something to differentiate you from the pack.”