In Frederick Wiseman’s “High School” (1968), we are given a 75-minute glimpse into what life was like for students and faculty at Northeast High School in Philadelphia in the spring of 1968. The factory-esque campus, the brazenly curt interactions between teachers and students, the Coke-bottle reading glasses — all vividly seen but never narrated.

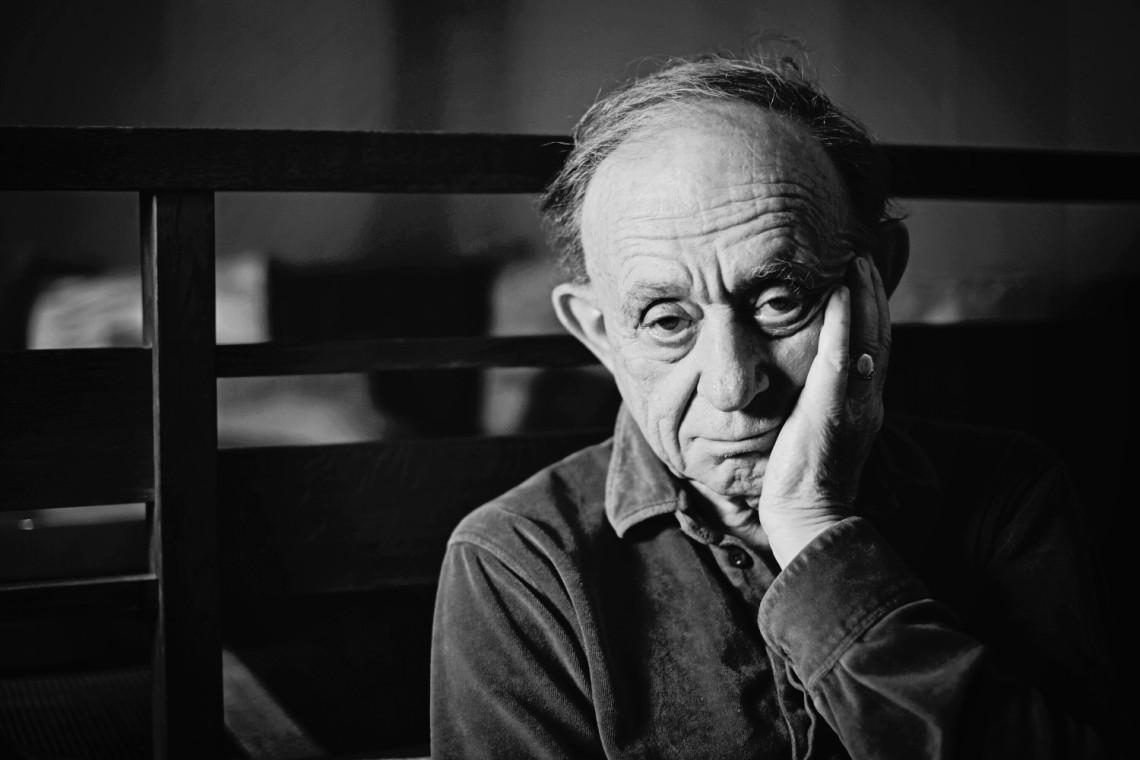

Late last week, Wiseman, 88, was kind enough to attend a live Q&A after a screening of the film at Sonoma State’s Warren Auditorium. Unsurprisingly, it was difficult to find an open spot in the 200-person seating arrangement.

Wiseman has been a prominent figure in the film business for some 50-plus years with 44 documentaries and counting, something he admits was never his original intention. “I was bored with what I was doing, which was teaching law, and I reached the age of 30 and I figured I’d better do something I liked before I was an unhappy old man,” he told the audience, “And I’m an old man now.”

It would be an understatement to say that the world of documentary filmmaking, and filmmaking as a whole, would have been vastly different if Wiseman had never made that pivotal career shift in his 30’s. From his first documentary “Titicut Follies” (1967), about a hospital for the criminally insane, to his latest work, “Monrovia, Indiana” (2018), which debuted over the weekend at the New York Film Festival, Wiseman has focused primarily on the exploration of American institutions.

When asked to expand on a joke he made in which he said it “only seemed logical” to follow up a documentary on a hospital for the criminally insane with a documentary about high school, Wiseman was reluctant to do so. “Well, no. I mean, it’s a bad joke. It kills the joke to expand on it,” he said. But the parallels are there, and hard to ignore.

The structuring of Wiseman’s films are often what sets him apart from other popular “direct cinema” or “cinema verite” filmmakers of the 1960s, and “High School” is no exception.

Adopting a “day in the life” format, the viewer is led through an arrival at the school, opening “thought of the day” dialogues from teachers, gym classes, meetings with the vice principal, cafeteria and lunch breaks, etcetera. Do not refer to this as a “fly-on-the-wall” perspective, though. “It’s an insulting term,” he said jokingly, “Most flies I know aren’t conscious at all, and I like to think I’m at least 2 percent conscious.”

Indeed he is. While Wiseman set out to make a film about high school as an institution, he admits that certain aspects of the film’s agenda only arose through keen observation in post-production. “One of the principal themes of the movie, which only emerged in the course of the editing, was how values are passed on from one generation to another.”

This idea is driven home by the insistence of the faculty to emphasize a conformist attitude among students, even going so far as to tell one student that there is “a time and place for being individualistic.” The student must then apologize.

It has been 50 years since “High School” debuted, and when asked about the audience’s perception of the film still being an accurate depiction of high school today, Wiseman did not disagree. “It’s depressing,” he said, eliciting a bit of laughter from the packed auditorium.

Shortly after his Q&A, Wiseman was scheduled to get on a flight to New York for the debut of his latest project, which Variety critic Guy Lodgeconsiders “among his most invaluable recent works.” We can safely assume Wiseman’s prominence as a documentarian, however happenstantial a career it may have been, will continue.