According to a recent poll, nearly two-thirds of Americans say fake news causes confusion about current events.

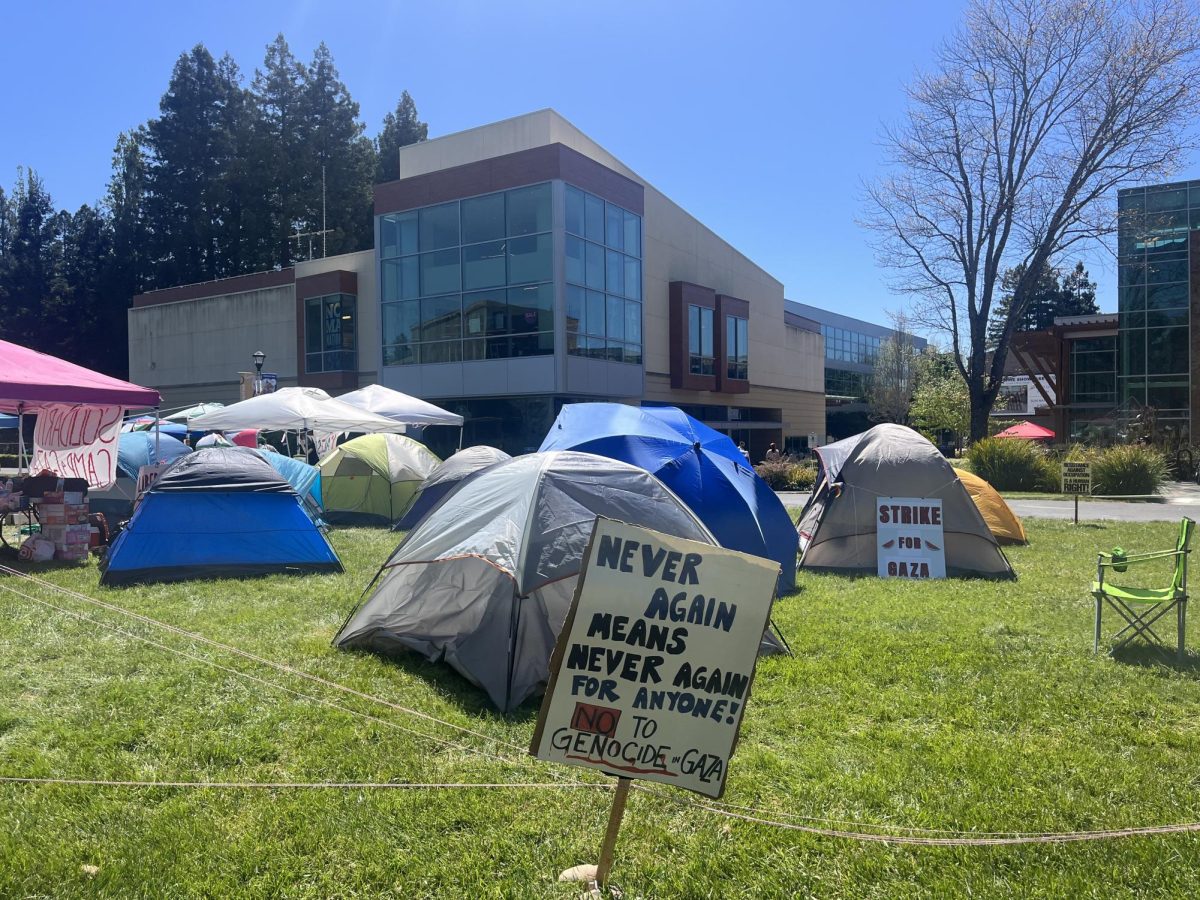

But what can we do about it, and how do readers identify fake news when they see it on social media? These were some of the issues discussed in Ballroom D on Tuesday, as a panel discussion featuring The Press Democrat, First Amendment Coalition and Sonoma State University came together to discuss fake news, specifically how we can regulate within the First Amendment and what the media can do to combat it.

The panel, which included (left to right) Annika Toernqvist, Dave McCuan, Karl Olson and David Snyder, discussing the First Amendment and the rise of fake news, especially on social media.

Titled “Fake News and the First Amendment,” the panel included Annika Toernqvist, digital director for Sonoma Media Investments at The Press Democrat, Sonoma State political science professor Dave McCuan, David Snyder, executive director of the First Amendment Coalition based in San Rafael and First Amendment attorney Karl Olson. Paul Gullixson, editorial director for The Press Democrat, and faculty adviser to the Sonoma State STAR, moderated the discussion.

According to Snyder, fake news isn’t a new entity, but there is something different about the current version of it. He accounts this change to both structural and social causes.

“We no longer have the gatekeeper organizations, such as The New York Times, ABC News and CBS News, to keep truly ridiculous and false information out of circulation,” Snyder said. “With social media people pay less attention to where things are coming from while paying more attention to things they want to see.”

This modern consumption of news brought forth the discussion of social media accounts being created, many times by foreign entities, simply for the sharing of news stories that are deliberately fake. According to Gullixson, ‘bots,’ or algorithms that act like real social media users, are bought to promote tweets, giving an impression that it’s been viewed by thousands, possibly giving false credibility to the source of the tweet.

When comparing this fact to fake news’ role in the 2016 election, McCuan said, “This is paradigm shattering.”

According to McCuan, political transparency and disclosure are gone, and there is no longer a way to find out who is funding these bots, which are capable of getting information off just about anybody in the United States. This information, which is sometimes classified, directly correlates to the news stories an individual sees on their social media feed, McCuan said.

“Campaigns can drive messages to you that are fundamentally different, especially with the rise of bots,” McCuan said, “which is why this is different, because it’s difficult to ascribe transparency and legislation for what’s going on, especially when looking at the First Amendment.”

The First Amendment, according to Olson, protects erroneous statements, which generally protects most fake news. However, Snyder said the introduction of many 2016 California bills trying to combat fake news, even though almost all did not pass, shows an irrationality in today’s society.

“The election of President Trump has caused people to become hyper-emotional in a way that makes them forget what our founding documents are about,” Snyder said. He noted that one bill in particular that the California Legislature considered earlier this year, that sought to make fake news illegal, also would have prevented many forms of free speech, particularly speech in political campaigns where embellishment frequently occurs.

As media outlets try to change the momentum of fake news, the difficulty of covering stories not dealing with fake news itself has become more challenging.

“We spend so much time dealing with fake news and trying to argue the facts and the truth that we should be well past, that it leads to real news not being covered,” said Gullixson, speaking of his experience at The Press Democrat.

Looking towards possible solutions for fake news comes with a variety of answers but no real solution. According to Snyder, a way to combat fake news is for traditional news outlets to “keep doing what they’re doing but better than they’ve ever done it before.” However, a problem may lie in the line that separates opinion from news and people’s ability to distinguish one from the other.

“What we’re challenged to do is teach people how to exercise judgment,” McCuan said. “Whether you are online or reading a newspaper, this a terribly difficult task…so anything that advances us, whether it be legislatively or a principle, that can add to teaching judgment is going to lead to civic discourse.”

Toernqvist noted that people have to make an effort to find out if they can trust a story or not.

When looking at a story, Toernqvist recommends looking at the author’s credentials, checking if the site the article was found on has an archive and looking for credible sources within the story. She also recommends using sites like Snopes.com to check out a story’s validity, as well as using sites such as politifact.com or factcheck.org for fact checking within a story.

Additionally, search engines such as Google and Bing now flag users when they deem a story as illegitimate. Some sites are also using Snopes.com to let readers know a story has been proven “false,” and Facebook has begun alerting readers of facts within a story that some have disputed.

The Press Democrat suggests checking the sources of stories, especially if it’s not a well-known news organization, looking at URLs, as the Press Democrat notes that stories with a com.co or com.lo URL are most likely fake, and being wary of attention-grabbing headlines without a source.