After winning a gold medal, a record-breaking sprinter also broke cultural norms at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, making U.S. citizens more aware of their country’s flawed racial relations in the process.

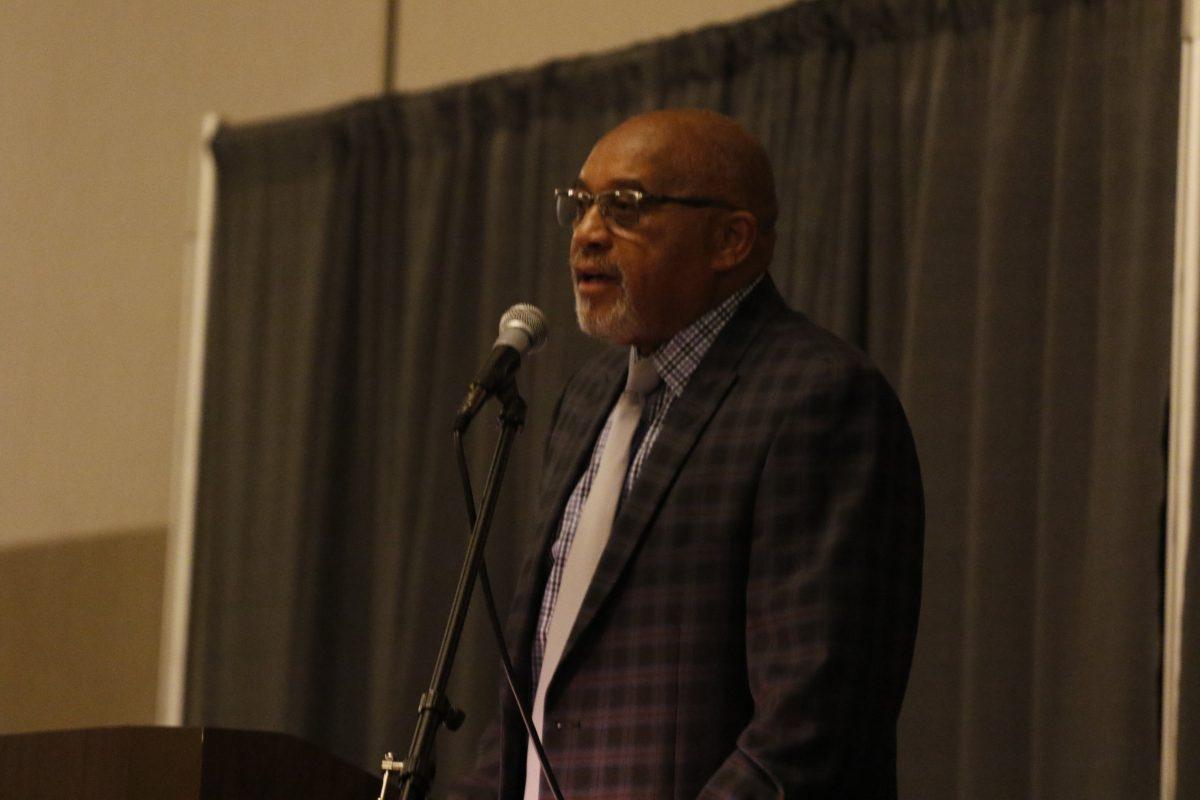

Tommie Smith, the sprinter who broke the 20-second record for the 200-meter race that year, shared his life story and experiences with a crowd of Sonoma State University students on April 11 in the Student Center. He was the last featured speaker in the 2017 Sonoma State Sport and Social Justice Lecture Series.

Smith is best known for the political statement he made after winning the 200-meter gold medal at the 1968 Olympics. Wearing no shoes with black socks and a black scarf while receiving the medal, he raised a black-gloved fist during the National Anthem to protest poverty and discrimination against African-Americans, according to an archived BBC article.

Lauren Morimoto, kinesiology professor and director of diversity and excellence at Sonoma State, introduced Smith. She said his actions in 1968 inspired her to study race relations in sports as a graduate student.

“If you pick your heroes well, they won’t disappoint you,” Morimoto said. “Dr. Tommie Smith has shown that he is as thoughtful, committed, political [and] educational as he seemed back in 1968.”

Smith began his speech by acknowledging Sonoma State was a “more relaxed” platform for making a statement than the Olympics. He discussed his early years in a family who moved from Clarksville, Texas to Stratford, California in 1951.

Before moving to California, Smith said he attended an all-black grammar school where one instructor taught all the grade levels. This was before Rosa Parks’ act of civil disobedience in 1955, so Smith said he was never told he could sit in the front of the classroom.

“I received no encouragement, civil or human,” Smith said. “These liberties were nonexistent. There was no mention of black history or black pride in any books.”

In the years leading up to his participation in the Olympics, Smith said he worked in the fields 12 hours per night and attended classes during the day. He said when he graduated from high school, he didn’tknow he “was being groomed to stand for social justice on the world’s platform” at the Olympics.

“I am very blessed to have stood at a time when standing for social equality was not a safe indulgence at 24-years-old,” Smith said.

Smith faced persecution and threats on his life when he returned from the U.S after the 1968 Olympics. He said he spent money on locks to protect his car after receiving numerous bomb threats.

In spite of the adversity he faced after protesting racial inequality, Smith stressed the importance of working to provide a good example for children, who often idolize athletes, he said.

Smith said people who value social activism need to be able to explain why they stand for a particular cause.

“I pity the person who [opts] to accept ignorance in the face of adversity,” Smith said. “You have a responsibility—you have a grave responsibility.”

Angelique Lopez, finance and budget coordinator for Sonoma State’s Black Student Union, said Smith’s speech encouraged activism for rights that too often go unnoticed.

“It was something we’ve been needing…it was encouraging in the sense that it empowers us to be more active on campus,” Lopez said.

Morimoto, who created the Sport and Social Justice Lecture Series through Sonoma State’s IRA funds, was instrumental in Smith visiting the campus. She said she reached out to Smith since he had a unique perspective among the scheduled speakers given his activism in the 1960s.

“He was probably one of the most visible athletes to first use his platform to make a political statement,” Morimoto said. “So in many ways, he is groundbreaking, and I think for others who might not be as overt in their activism…he could give us a sense of what was at risk.”

Morimoto said she liked the amount of student participation during a Q&A session that followed Smith’s speech. Some of the questions asked during this time drew connections between Smith’s 1968 protest and recent activism from 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick.

While answering a student question during the Q&A, Smith said he felt Kaepernick’s protest was in response to recent police brutality against African-Americans.

Smith said there is no one proper way to make a stand through activism.

“There is no best [approach], there is a choice,” Smith said. “You pick your choice, and it might work for you, it might not. But you get a message out.”

Morimoto said she hopes Smith’s protest will convince Sonoma State students that “one person raising their voice can make a difference.”

“We all have choices to make,” Morimoto said.” Are we going to put our [fists] up and say things are not OK…or are we going to keep our [fists] down and collect our gold medal and call it a day?”