Beauty is in the eye of the beholder; chances are you’ve heard this saying more times than you can count. In fact, you were likely instilled with this nugget of conventional wisdom before you were old enough to have developed a sense of self. You might have even embraced this idiom as a personal motto in an effort to survive the agonizing torment that life can be. I know I’ve certainly been comforted by its powerful message more than a few times.

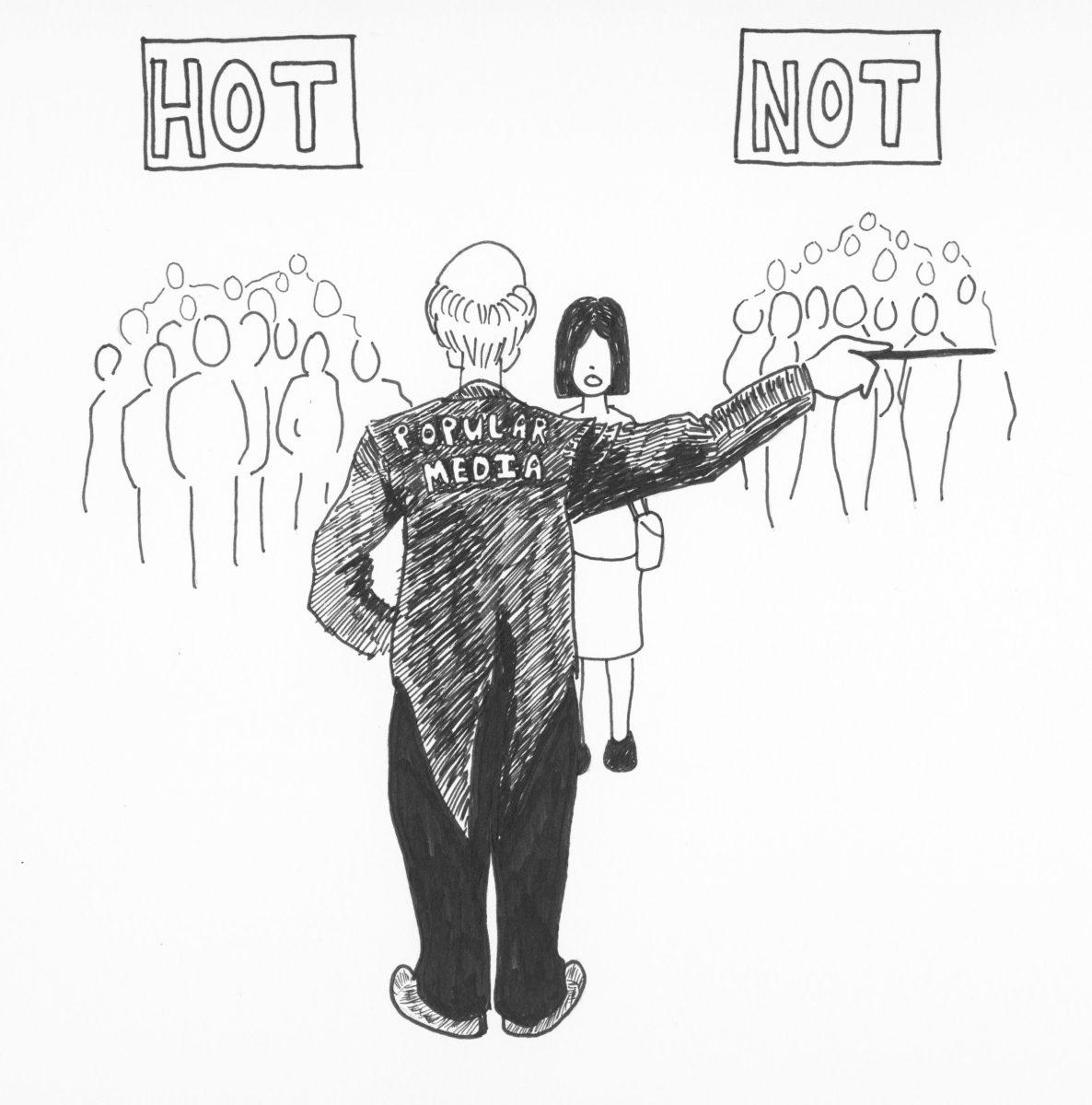

But does this phrase actually carry any truth in our society, or is it nothing more than empty words of consolation used to soothe the stricken spirit? Although beauty is said to be subjective, there is an undeniable hierarchy of physical appearance at play in America, and our current era of media-driven domination is mostly to blame.

In our society today, being anything less than a size two model with a body devoid of hair and a head full of the luscious stuff renders you an inferior person. Thus, I believe that beauty is not so much in the eye of the beholder as it is in the eye of the dominant culture.

Of course, this bold statement is underscored by a recognized bias of mine: the painful, societally-enforced fact that I am neither skinny nor hairless. However, I am nowhere near the only person who has felt the crushing weight of our judgmental populace.

“I don’t know what things are like in non-consumer, more egalitarian societies built around other structures of power than economic power,” said Scott Miller, a professor at SSU, “but in our late-capitalist consumer economy the body, like everything else, becomes a commodity—‘goods’ that we have no choice but to sell at the best rate we can.”

Miller, speaking from personal experience and observation, added, “This dynamic sets us up for all the anxiety and suffering we see. The media is just an expression of the system—kind of like a mercenary force that does the dirty work.”

Our documented history certainly supports Miller’s assertions. For centuries, we have seen an inordinate amount of discrimination of individuals based upon race, gender, sexuality, and religion. But what about looks?

Well, according to Daniel S. Hamermesh, Ph.D, the discriminative inequalities which less than attractive people face in our society are extremely similar to those that minorities still face. In his book “Beauty Pays,” Hamermesh claims that being unattractive will get you a lower paycheck.

Based on the results of a study of American workers whose looks were graded by casual observers, those who ranked in the bottom one-seventh earned between 10 to 15 percent less than the workers who made the top one-third. That’s a lifetime difference in pay of about $230,000 – not an encouraging statistic.

“In the workplace, we are unconsciously drawn to people who are more attractive, because we assume they have their act together and will be more successful,” said Psychiatrist Carole Lieberman.

But what about the educational system? Surely the appearance bias cannot occur there, apart from the inevitable bullying and rejection which unattractive children seem to invite? Well, a classic college study proves differently. In this study, psychologists David Landy and Harold Sigall asked participants to rate two identical essays.

However, they also included a photo of the author, showing him or her to be either attractive or unattractive. Despite the fact that the essays were exactly the same, those attached with an attractive photograph got a significantly higher rate than essays paired with an unattractive photograph.

Is it too late to tell the editors to scrap my mugshot with this piece?

Throughout all of this, one thing remains painfully clear: the ambiguous nature of the definitions of beauty and ugliness. Hopefully most of us acknowledge that beauty is not entirely in the eye of the beholder – not when you take the inevitable, hegemonic workings of our society into account.

It only follows that ugliness isn’t completely subjective either. What is considered “beautiful” and what is deemed “ugly” in America is largely determined by the dominant, media-driven culture. So what can we do to remedy this situation?

“I think the only way to fix it is for people to realize that these [celebrities] we see all over the place are unrealistic representation of men and women. We need more relatable role models, like Adele or Jennifer Lawrence, if we really want to try to make a change,” said freshman Katrina Romero, who thinks that the solution lies in the representation of celebrities we so desperately worship in the appearance-driven media.

I agree and would like to add that the awareness of our tendency to enforce an unattainable standard of beauty upon all vestiges of society is the key to stopping it.

Miller said that “an understanding that the social organization that breeds the beauty regime is arbitrary and mistaken and extremely partial and therefore to be treated with resignation at best and often derision and a strong critical attitude” can help.

In America, beauty unfortunately seems to be in the eye of the dominant culture. So let’s change that culture to reflect the uplifting idioms we were taught to believe.

After all, why should looks matter so much anyway? It’s what’s on the inside that counts.