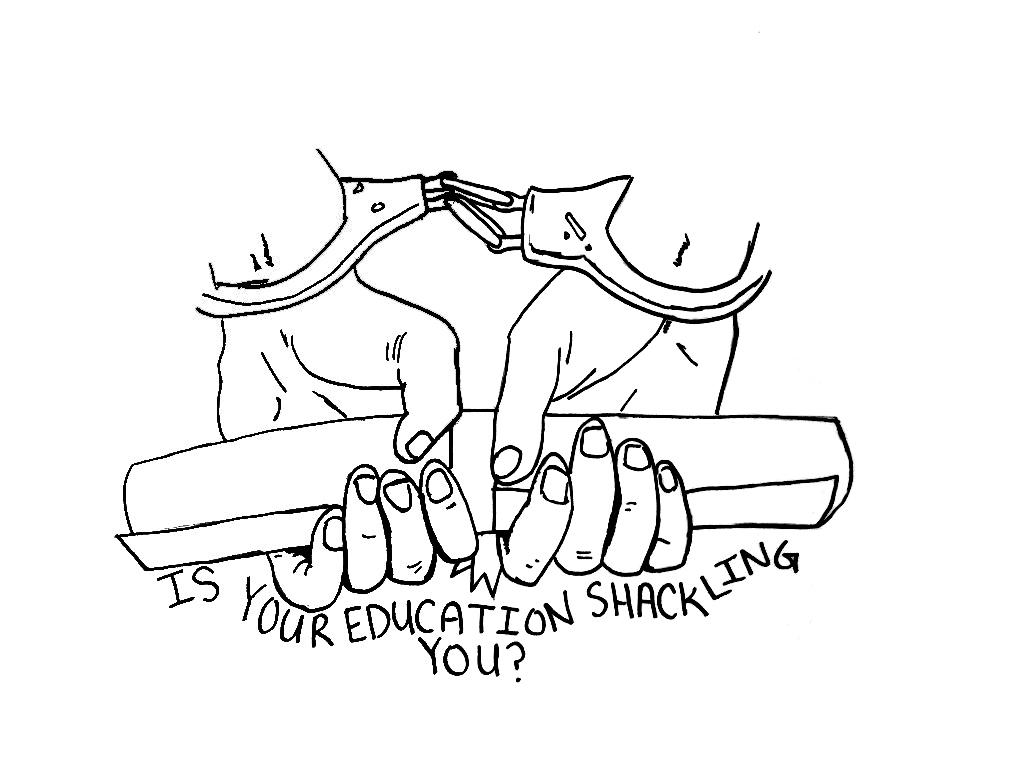

School is killing creativity, and here’s why.

From the beginning, children grow up taking courses like English and mathematics every year, and as they get older, have little chance to branch out into other subjects they have more passion for. Even when college comes around, students still need to take courses they are uninterested in just to prove one can get through it all.

Teachers usually anticipate parallel reactions in general education when asking students to introduce themselves and why they’re taking a class—“because I needed upper division GE.”

Now, what is the point in proving someone can write a five-paragraph essay?

Furthermore, Sonoma State University requires students to pass the Written English Proficiency Test to graduate, which is equivalent to proving whether or not someone took an English class throughout their entire life.

An effective alternative is evaluating which students actually struggle with writing, and advising them to take courses or encourage tutoring to improve their skills. Sure, writing is a vital skill in many careers, but not everyone is interested and planning to go into a field that requires it.

Also, instead of end-of-semester Student Evaluations of Teaching Effectiveness surveys, students deserve the opportunity to grade their teachers on a weekly basis.

This could include a five-minute form to rate interest level, teaching ability, engagement, etc. How often do teachers get to go through and truly appreciate constructive criticism when they are flooded with such surveys at the end of the semester?

According to a 2012 study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, primary teachers in the U.S. spend nearly 1,100 hours a year teaching, with lower secondary instructors around 1,070 hours and upper secondary at about 1,050 hours.

Despite all this time teaching, the U.S. falls behinds in average reading, mathematics and science literacy scores compared to other countries, as evident in the 2012 Program for International Student Assessment.

One example of a country which excels is Finland, which has some of the highest test scores—not to mention minimal standardized testing and smaller classrooms.

More importantly, teachers are required to have a master’s, and are held on the same scale as doctors and lawyers. The country also doesn’t have separate classrooms for accelerated learning or special education.

Students have little to no homework until their teens, have an average of 75 minutes a day of recess rather than 27 in the U.S. and the only required standardized test is taken at age 16.

Instead of requiring high schoolers to pass a civics test to graduate like Arizona is doing, the U.S. needs to restructure and balance its priorities for students and teachers.

Some teachers don’t believe in homework, others aren’t allowed to show films in class. School boards don’t like their instructors to show students movies that don’t have anything to do with the curriculum, arguing they are for home life, which needs to be separate from school life. So then, why give students homework?

Whoever has the answer to that argument is encouraged to respond during office hours, because there obviously isn’t enough time to address it during a three-and-a-half-hour class.