A controversy on campus about the potential health risks of asbestos in some of Sonoma State University’s older buildings is rooted in a lawsuit filed by a former environmental health and safety inspector who resigned in July 2015 after raising concerns about asbestos and other issues on campus.

The specialist, Thomas Sargent, who is a “certified asbestos consultant,” filed a lawsuit in November against the Board of Trustees of the California State University and his former supervisor, Director of Energy and Environmental Health and Safety Craig Dawson.

In his allegations, Sargent claims to have been a victim of retaliation for being a whistleblower to the mishandling of material, including lead paint chips, that may have put student and faculty health at risk. His lawsuit is scheduled to go to trial in July. Sargent has declined to comment on the lawsuit or the controversy over the asbestos testing. His attorney also declined to comment as well, referring thereporter to the lawsuit itself.

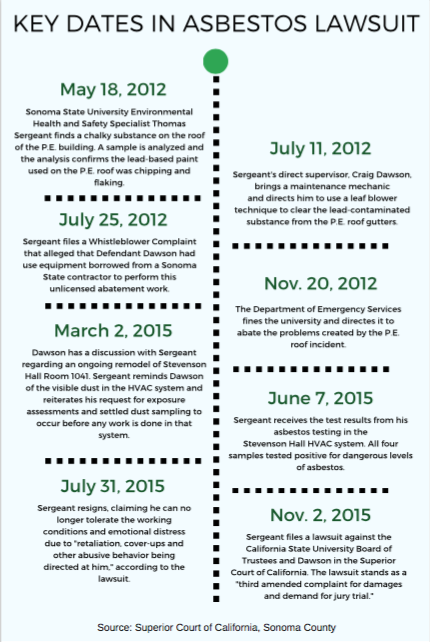

The lawsuit contends the problems began on May 18, 2012 when Sargent detected a “chalky substance” on the roof of the Physical Education building. His suspicions the substance may have contained lead paint were confirmed when he had the sample analyzed. According to the lawsuit, when he raised concerns about the contaminated paint on the roof of the building chipping and flaking and said that it needed to be handled with skill during plans to reroof the building, he was told by Dawson, “you caused too much alarm with your regulatory email . . . it will kill the project with costs.”

According to the lawsuit, Sargent suggested the removal of the substance using a vacuum in order to ensure the lead-contaminated chalk would not disperse to other areas. The suit contends San Francisco-based CPM Environmental gave the university a quote, saying it could clear the lead-contaminated chalk from the P.E. roof for $1,604.

The lawsuit asserts Dawson denied this approach and instead assigned a worker to use a leaf-blowing technique that allegedly dispersed the lead-containing material putting the health of students, faculty, daycare children and other visitors who regularly pass by the P.E. building in danger.

Dawson declined to comment when asked by the STAR about these accusations.

According to the allegations, when Sergeant became aware of Dawson’s actions, he contacted the California Department of Public Health Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Branch, CalOSHA and Sonoma Department of Emergency Services. The California Division of Occupational Safety and Health cited Sonoma State for “violating its lead standards” on Nov. 20, 2012. In addition, the Department of Emergency Services fined the university and directed it to abate the problems created by the P.E. roof incident.

In his lawsuit, Sargent further alleged that Dawson ignored his warnings for over a decade, which resulted in dangerous levels of asbestos dust from abraded floor tiles throughout the faculty office buildings in Stevenson Hall. After blowing the whistle about these issues, Sergeant said he endured almost two years of what the lawsuit describes as “harassment, discrimination, and retaliation,” from both the university and his supervisors and, for that, he is now seeking more than $2 million in damages.

However, Sargent’s actions also opened a pandora’s box for Sonoma State’s administration.

His allegations include the potential knowledge of air contamination of six different buildings, including Stevenson Hall, with asbestos-containing dust traveling through the heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems, as well the removal of asbestos-containing tiles from the private bathroom of Sonoma State President Ruben Armiñana.

Sonoma State’s administration has publicly acknowledged the presence of asbestos in the following buildings: Art Department, Carson Hall, Children’s School, Commons, Facilities Services, Food Services, Ives Hall, Kinesiology/P.E. Building, Nichols Hall, Zinfandel, Student Health Center, Student Union, among others.

This is no surprise, since, according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, every building built before the late 1970s was constructed with asbestos-containing materials. However, in the case of Sonoma State’s buildings, the question is whether the asbestos structures are being disrupted, and if they are present in the airstudents, faculty and staff breathe, as alleged in Sargent’s lawsuit.

“We have had an asbestos management program since at least the early 1990s,” said Dawson. “Managing asbestos in place is the main protocol until asbestos renovations and removal are performed in the buildings.”

According to the EPA, asbestos disruptions can occur by the demolition, maintenance, repair or remodeling of an asbestos-containing building. However, asbestos in Stevenson Hall are found in a large majority on the tiles.

This means simply walking and chair rolling can potentially be releasing asbestos into the air.

This possibility has been unsettling for some faculty and students, some of whom have opted not to use offices or classrooms in Stevenson.

In order to protect people, Dawson says his department has installed a layer of epoxy-protective and highly durable plastic material on the tile, as well as plastic floor mats under rolling chairs.

Sonoma State’s website shows reports of asbestos testing since 2013, all of which was performed on the air, according to Dawson, “All hazard associated to being exposed to asbestos happen from inhalation.” The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has an 8-hour asbestos exposure limit at 0.100 fibers per cubic centimeter. The results from 2013 range from 0.062 fibers to less than 0.001 or “non-detectable amounts.”

Nevertheless, some faculty in Stevenson, including Sociology Professor Peter Phillips, have complained about high amounts of dust that, like the lawsuit alleged, “contain high levels of asbestos.”

Independent testing by Sacramento-based HB&T Environmental Incorporated was performed in different buildings including Stevenson, Carson and Nichols in July of 2015.

According to the results, after testing the West Vertical Return Air Shaft of the third floor of Stevenson, up to 518,000 asbestos structures per square centimeter were found.

The Northeast Vertical Return Air Shaft, also in the third floor of Stevenson is reported to contain 259,000 asbestos structures per square centimeter, according to the independent test.

According to a representative from an outside asbestos lab based in Sacramento, the reason these numbers differ is because of the different methods of testing used by each company.

The numbers published by HB&T are not only differing to the reports conducted by the school’s administration, but also potentially alarming since levels above 100,000 structures per square cm are considered high, as stated by the independent report.

“Sonoma State testing claims the air is clean, but the independent reports say the intake ducts are covered with asbestos,” said Sonoma State Math Professor Sam Brannen, who also serves on the Academic Senate. “You can’t get onto surfaces without going through the air first.”

In response to the lawsuit, the school’s administration has conducted monthly testing from June 2015 to March 2016. All of the air testing results have come back negative.

However, on June 19 of last year, five out of eight settled dust samples had detectable levels of asbestos.

Another allegation in Sargent’s lawsuit is that asbestos-containing tile was removed from Armiñana’s office in Stevenson Hall. According to the lawsuit, Armiñana himself requested to have them removed

However, Armiñana contends the claims that he was putting concerns about his health above the interests of others as false.

“Not true,” said Armiñana, “the tiles were removed because my toilet was replaced for a low-flow toilet due to water conservation purposes.”

“[The tiles in Armiñana’s office] were stained,” said Associate Director of Marketing and Communications Susan Kashack. “The facilities people did it, and they would have blocked off windows and have vents if asbestos were present.”

According to the lawsuit, “virtually all of the offices in the five remaining asbestos-contaminated buildings have not been cleaned.”

A series of motion hearings are scheduled to take place before the lawuit goes to trial in July. The first of which is scheduled for April 13 in Sonoma County Superior Court.